Introduction

The 19th century was the time of the largest geographical discoveries made by Russian explorers. Continuing the traditions of their predecessors - explorers and travelers of the 17th-18th centuries, they enriched the ideas of Russians about the world around them, contributed to the development of new territories that became part of the empire. Russia for the first time realized an old dream: its ships went to the oceans.

The purpose of my work is to study and determine the contribution to the development of geography - works, expeditions, studies of Russian circumnavigations.

The first Russian round-the-world trip of I.F. Kruzenshtern and Yu.F. Lisyansky

In 1803, at the direction of Alexander I, an expedition was undertaken on the ships Nadezhda and Neva to explore the northern part of the Pacific Ocean. It was the first Russian round-the-world expedition that lasted 3 years. It was headed by Ivan Fedorovich Kruzenshtern, the largest navigator and geographer of the 19th century.

Small ships were purchased from the UK. Before sailing, Emperor Alexander I personally examined the sloops purchased from the British in Kronstadt. The sovereign allowed military flags to be hoisted on both ships and accepted the costs of maintaining one at his own expense, while the Russian-American Company and one of the main inspirers of the expedition, Count N.P., paid for the other. Rumyantsev.

The first half of the voyage (from Kronstadt to Petropavlovsk) was marked by the eccentric behavior of Tolstoy the American (who had to be landed in Kamchatka) and the conflicts of I.F. Kruzenshtern with N.P. Rezanov, who was sent by Emperor Alexander I as the first Russian envoy to Japan to establish trade between countries.

The expedition left Kronstadt on July 26 (August 7), 1803. She called at Copenhagen and arrived at Falmouth on September 28, where she had to once again caulk the entire underwater part of both ships. Only on October 5, the expedition went further south, went to the island of Tenerife; On November 14, at 24° 20" west, she crossed the equator. The Russian flag flew for the first time in the southern hemisphere, which was celebrated with great solemnity.

Having reached 20 ° south latitude, Kruzenshtern searched in vain for Ascension Island, the position of which was very inconsistent. The repair of the Neva ship forced the expedition to stay off the Brazilian coast from December 9 to January 23, 1804. From here, the navigation of both ships was at first very successful: on February 20, they rounded Cape Horn; but soon strong winds with hail, snow and fog met them. The ships parted and on April 24 Kruzenshtern alone reached the Marquesas Islands. Here he determined the position of the islands of Fetuga and Uaguga, then entered the port of Anna Maria on the island of Nukagiva. On April 28, the Neva ship also arrived there.

On the island of Nukagiva, Kruzenshtern discovered and described an excellent harbor, which he called the port of Chichagov. On May 4, the expedition left the Washington Islands and on May 13, at 146 ° west longitude, again crossed the equator towards the north; On May 26, the Hawaiian (Sandwich) Islands appeared, where the ships separated: Nadezhda headed for Kamchatka and further to Japan, and Neva went to explore Alaska, where she took part in the Arkhangelsk battle (Battle of Sitka).

Taking from the ruler of the Kamchatka region P.I. Koshelev guard of honor (2 officers, drummer, 5 soldiers) for the ambassador, "Nadezhda" headed south, arriving in the Japanese port of Dejima near the city of Nagasaki on September 26, 1804. The Japanese forbade entering the harbor, and Kruzenshtern anchored in the bay. The embassy lasted six months, after which everyone returned back to Petropavlovsk. Kruzenshtern was awarded the Order of St. Anna II degree, and Rezanov, as having completed the diplomatic mission entrusted to him, was released from further participation in the first round-the-world expedition.

"Neva" and "Nadezhda" returned to St. Petersburg by different routes. In 1805, their paths crossed at the port of Macau in southern China. "Neva" after calling on Hawaii assisted the Russian-American company headed by A.A. Baranov in recapturing the Mikhailovskaya fortress from the natives. After an inventory of the surrounding islands and other studies, the Neva took the goods to Canton, but on October 3 ran aground in the middle of the ocean. Lisyansky ordered the rosters and carronades to be thrown into the water, but after that a squall landed the ship on a reef. To continue sailing, the team had to throw into the sea even such necessary items like anchors. Subsequently, the goods were picked up. On the way to China, Lisyansky's coral island was discovered. The Neva returned to Kronstadt before the Nadezhda (July 22).

Leaving the shores of Japan, Nadezhda went north to the Sea of Japan, almost completely unknown to Europeans. On the way, Kruzenshtern determined the position of a number of islands. He passed through the La Perouse Strait between Iesso and Sakhalin, described the Aniva Bay, located on the southern side of Sakhalin, the eastern shore and Patience Bay, which he left on May 13. A huge amount of ice that he met the next day at 48 ° latitude prevented him from continuing his navigation to the north and he went down to the Kuril Islands. Here, on May 18, he discovered 4 stone islands, which he called "Stone traps"; near them, he met such a strong current that, with a fresh wind and a speed of eight knots, the ship "Nadezhda" not only did not move forward, but she was carried to an underwater reef.

With difficulty, having avoided trouble here, on May 20, Krusenstern passed through the strait between the islands of Onnekotan and Haramukotan, and on May 24 he again arrived at the Peter and Paul port. June 23 he went to Sakhalin. To complete the description of its shores, 29 passed Kurile Islands, the strait between Raukoke and Mataua, which he named Hope. July 3 arrived at Cape Patience. Exploring the shores of Sakhalin, he went around the northern tip of the island, descended between it and the coast of the mainland to a latitude of 53 ° 30 "and in this place on August 1 he found fresh water, according to which he concluded that the mouth of the Amur River was not far, but because of the rapidly decreasing depth, go decided not to move forward.

Sloop "Hope".

The next day he anchored in the bay, which he called the Bay of Hope; On August 4, he went back to Kamchatka, where the repair of the ship and replenishment of supplies delayed him until September 23. When leaving the Avacha Bay due to fog and snow, the ship almost ran aground. On the way to China, he searched in vain for the islands shown on old Spanish maps, weathered several storms, and arrived in Macau on November 15. On November 21, when the Nadezhda was already quite ready to go to sea, the ship Neva arrived with a rich cargo of fur goods and stopped in Whampoa, where the ship Nadezhda also moved. At the beginning of January 1806, the expedition ended its trading business, but was detained by the Chinese port authorities for no particular reason, and only on January 28 did the Russian ships leave the Chinese shores.

Leaving the Sunda Strait, the ship "Nadezhda" again, only thanks to the rising wind, coped with the current into which it fell and which carried it to the reefs. April 3 "Nadezhda" parted from the "Neva"; 4 days later, Krusenstern rounded the cape Good Hope and on April 22 he arrived on the island of St. Helena, having traveled from Macau in 79 days, after 4 days Krusenstern left and on May 9 again crossed the equator at 22 ° west longitude.

Even on the island of St. Helena, news was received about the war between Russia and France, and therefore Kruzenshtern decided to go around Scotland; On July 5, he passed between the Fair Isle and Mainland islands of the Shetland archipelago and, having sailed for 86 days, arrived on July 21 in Copenhagen, and on August 5 (17), 1806 in Kronstadt, having completed the entire journey in 3 years 12 days. During the entire voyage on the ship "Nadezhda" there was not a single death, and there were very few sick people, while on other ships then many people died in inland navigation.

Emperor Alexander I awarded Krusenstern and his subordinates. All officers received the following ranks, commanders of the Order of St. Vladimir 3rd degree and 3,000 rubles each, lieutenants 1,000 each, and midshipmen 800 rubles a lifetime pension. The lower ranks, if desired, were dismissed and awarded a pension of 50 to 75 rubles. By royal order, a special medal was issued for all participants in this first round-the-world trip.

The description of this expedition was published at the expense of the imperial office under the title "Journey around the world in 1803, 1804, 1805 and 1806 on the ships Nadezhda and Neva, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Kruzenshtern", in 3 volumes, with an atlas of 104 maps and engraved paintings, St. Petersburg, 1809

This work has been translated into English, French, German, Dutch, Swedish, Italian and Danish. Reissued in 2007.

Kruzenshtern's voyage was an era in the history of the Russian fleet, enriching geography and the natural sciences with many information about countries little known. This voyage is an important milestone in the history of Russia, in the development of its fleet, it made a significant contribution to the study of the oceans, many branches of the natural sciences and the humanities.

Since that time, a continuous series of Russian round-the-world travels begins; In many ways, the management of Kamchatka has changed for the better. Of the officers who were with Kruzenshtern, many subsequently served with honor in the Russian fleet, and the cadet Otto Kotzebue was himself later the commander of a ship that went on a round-the-world trip.

During the voyage, more than a thousand kilometers of the coast of Sakhalin Island were mapped for the first time. Many interesting observations were left by the participants of the trip not only about the Far East, but also about other areas through which they sailed. The commander of the Neva, Yuri Fedorovich Lisyansky, discovered one of the islands of the Hawaiian archipelago, named after him. A lot of data was collected by the members of the expedition about the Aleutian Islands and Alaska, the islands of the Pacific and Arctic Oceans.

The results of the observations were presented in the report of the Academy of Sciences. They turned out to be so significant that I.F. Kruzenshtern was awarded the title of academician. His materials formed the basis of the book published in the early 1920s. "Atlas of the South Seas". In 1845, Admiral Krusenstern became one of the founding members of the Russian Geographical Society. He brought up a whole galaxy of Russian navigators and explorers.

Expedition route.

Kronstadt (Russia) - Copenhagen (Denmark) - Falmouth (Great Britain) - Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain) - Florianopolis (Brazil, Portugal) - Easter Island - Nukuhiva (Marquesas Islands, France) - Honolulu (Hawaii) - Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky (Russia) - Nagasaki (Japan) - Hakodate (Hokkaido, Japan) - Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk ( Sakhalin Island, Russia) - Sitka (Alaska, Russia) - Kodiak (Alaska, Russia) - Guangzhou (China) - Macao (Portugal) - Saint Helena (Great Britain) - Corvo and Flores Islands (Azores , Portugal) - Portsmouth (Great Britain) - Kronstadt (Russia).

The history of Russia is connected with many Russian sea expeditions of the 18th–20th centuries. But a special place among them is occupied by round-the-world voyages of sailing ships. Russian sailors later than other European maritime powers began to make such voyages. By the time the first Russian circumnavigation of the world was organized, four European countries had already made 15 such voyages, starting with F. Magellan (1519–1522) and ending with the third voyage of J. Cook. Most of the round-the-world voyages on account of English sailors - eight, including three - under the command of Cook. Five voyages were made by the Dutch, one each by the Spaniards and the French. Russia became the fifth country in this list, but in terms of the number of round-the-world voyages, it surpassed all European countries combined. In the 19th century Russian sailing ships made more than 30 full round-the-world voyages and about 15 semi-circumnavigations, when the ships that arrived from the Baltic to the Pacific Ocean remained to serve in the Far East and Russian America.

Failed expeditions

Golovin and Sanders (1733)

For the first time in Russia, Peter I thought about the possibility and necessity of long-distance voyages. He intended to organize an expedition to Madagascar and India, but did not manage to carry out his plan. The idea of a round-the-world voyage with a call to Kamchatka was first expressed by the flagships of the Russian fleet, members of the Admiralty Board, Admirals N. F. Golovin and T. Sanders in connection with the organization of the Second Kamchatka Expedition. In October 1732, they submitted to the Senate their opinion on the expediency of sending an expedition "from St. Petersburg on two frigates through the Great Sea-Okiyan around the Gorn cap and into the Western Sea, and between the Japanese islands even to Kamchatka."

They proposed to repeat such expeditions annually, replacing some ships with others. This was supposed to allow, in their opinion, in a shorter time and better organize the supply of V. Bering's expedition with everything necessary, and quickly establish trade relations with Japan. In addition, a long voyage could become a good sea practice for officers and sailors of the Russian fleet. Golovin suggested that Bering himself be sent to Kamchatka by land, and he asked to entrust the navigation of two frigates to him. However, the ideas of Golovin and Sanders were not supported by the Senate and the opportunity to organize the first Russian voyage in 1733 was missed.

Krenitsyn (1764)

In 1764, it was decided to send around the world to Kamchatka an expedition of Lieutenant Commander P. K. Krenitsyn, but because of the impending war with Turkey, it was not possible to carry it out. The voyage, which I. G. Chernyshev, vice-president of the Admiralty Board, tried to equip in 1781, also did not take place. In 1786, the head of the "North-Eastern ... Expedition", Lieutenant Commander I. I. Billings (participant in Cook's third voyage), presented to the Admiralty Board the opinion of his officers that, at the end of the expedition, the return route of her ships would lie around Cape Good Hopes in Kronstadt. He was also denied.

But on December 22 of the same 1786, Catherine II signed a decree of the Admiralty Board on sending a squadron to Kamchatka to protect Russian possessions: ours to the lands discovered by Russian sailors, we order our Admiralty Board to send from Baltic Sea two ships armed, following the example of those used by the English captain Cook and other navigators for similar discoveries, and two armed boats of sea or other ships, at her best discretion, appointing them to bypass the Cape of Good Hope, and from there, continuing through the Strait of Sonda and leaving Japan on the left side, go to Kamchatka.

The Admiralty College was instructed to immediately prepare the proper instructions for the expedition, appoint a commander and servants, preferably from volunteers, make orders for arming, supplying and dispatching ships. Such a rush was associated with a report to Catherine by her secretary of state, Major General F. I. Soymonov, about the violation of the inviolability of Russian waters by foreigners. The reason for the report was the entry into the Peter and Paul Harbor in the summer of 1786 of a ship of the English East India Company under the command of Captain William Peters in order to establish trade relations. This was not the first time foreigners appeared in Russian possessions on pacific ocean, which caused the authorities to worry about their fate.

As early as March 26, 1773, Prosecutor General Vyazemsky, in a letter to the Kamchatka commandant, admitted the possibility of a French squadron appearing off the coast of Kamchatka in connection with the case of M. Benevsky. In St. Petersburg, news was received that a flotilla and 1,500 soldiers were being equipped in France for Benevsky. It was about equipping Benevsky's colonial expedition to Madagascar, in which twelve Kamchatka residents who fled with Benevsky also took part. But in Petersburg they suspected that, since Benevsky knew well the disastrous state of the defense of Kamchatka and the way there, this expedition could go to the peninsula.

In 1779, the governor of Irkutsk reported the appearance of unrecognized foreign ships in the area of the Chukotka nose. These were Cook's ships, heading from Petropavlovsk in search of a northwestern passage around America. The governor proposed to bring Kamchatka into a "defensive position", since the way to it became known to foreigners. The arrival of Cook's ships in the Peter and Paul Harbor in 1779 could not but alarm the Russian government, especially after it became known that the British put on their maps the American coasts and islands long discovered by Russian navigators and gave them their names. In addition, in St. Petersburg it became known that in 1786 the French expedition of J. F. La Perouse was sent on a round-the-world voyage. But it was still unknown about the expedition in the same year of Tokunai Mogami to the southern Kuril Islands, which, after collecting yasak Iv. Cherny in 1768 and the Lebedev-Lastochnik expedition in 1778-1779, Russia considered its own.

All this forced Catherine II to order the President of the College of Commerce, Count A. R. Vorontsov, and a member of the College of Foreign Affairs, Count A. A. Bezborodko, to submit their proposals on the issue of protecting Russian possessions in the Pacific Ocean. It was they who proposed sending a Russian squadron on a round-the-world voyage and declaring to the sea powers about the rights of Russia to the islands and lands discovered by Russian sailors in the Pacific Ocean.

Mulovsky (1787)

The proposals of Vorontsov and Bezborodko formed the basis of the above-mentioned decree of Catherine II of December 22, 1786, as well as the instructions of the Admiralty Board to the head of the first round-the-world expedition of April 17, 1787.

After discussing various candidates, 29-year-old Captain 1st Rank Grigory Ivanovich Mulovsky, a relative of the vice-president of the Admiralty College I. G. Chernyshev, was appointed head of the expedition. After graduating from the Marine cadet corps in 1774 he served twelve years on various ships in the Mediterranean, Black and Baltic Seas, commanded the frigates Nikolai and Maria in the Baltic, and then a court boat that sailed between Peterhof and Krasnaya Gorka. He knew French, German, English and Italian. After a campaign with Sukhotin's squadron in Livorno, Mulovsky was given command of the David of Sasunsky ship in Chichagov's squadron in the Mediterranean Sea, and at the end of the campaign was appointed commander of John the Theologian in Cruz's squadron in the Baltic.

The list of tasks of the expedition included various goals: military (fixing Russia and protecting its possessions in the Pacific Ocean, delivering fortress guns for the Peter and Paul Harbor and other ports, founding a Russian fortress in the southern Kuriles, etc.), economic (delivery of necessary goods to Russian possessions, livestock for breeding, seeds of various vegetable crops, trading with Japan and other neighboring countries), political (assertion of Russian rights to lands discovered by Russian sailors in the Pacific Ocean, by installing cast-iron coats of arms and medals depicting the Empress, etc.) , scientific (drawing up the most accurate maps, conducting various scientific studies, studying Sakhalin, the mouth of the Amur and other objects).

If this expedition were destined to take place, then now there would not be a question about the ownership of the southern Kuriles, seventy years earlier Russia could have begun the development of the Amur region, Primorye and Sakhalin, otherwise the fate of Russian America could have been formed. There were no round-the-world voyages on such a scale either before or since. At Magellan, five ships and 265 people participated in the expedition, of which only one ship with 18 sailors returned. Cook's third voyage had two ships and 182 crew members.

The squadron of G. I. Mulovsky included five ships: Kholmogor (Kolmagor) with a displacement of 600 tons, Solovki - 530 tons, Sokol and Turukhan (Turukhtan) - 450 tons each, and transport ship "Courageous". Cook's ships were much smaller: Resolution - 446 tons and 112 crew members and Discovery - 350 tons and 70 people. The crew of the flagship ship "Kholmogor" under the command of Mulovsky himself consisted of 169 people, "Solovkov" under the command of Captain 2nd Rank Alexei Mikhailovich Kireevsky - 154 people, "Falcon" and "Turukhan" under the command of lieutenant commanders Efim (Joachim) Karlovich von Sievers and Dmitry Sergeevich Trubetskoy - 111 people each.

The Admiralty Board promised the officers (there were about forty) extraordinary promotion to the next rank and a double salary for the duration of the voyage. Catherine II personally determined the procedure for rewarding Captain Mulovsky: “when he passes the Canary Islands, let him declare himself the rank of brigadier; having reached the Cape of Good Hope, to entrust him with the Order of St. Vladimir 3rd class; when it reaches Japan, he will already receive the rank of major general.

An infirmary for forty beds with a learned doctor was equipped on the flagship ship, and assistant doctors were assigned to other ships. A priest was also appointed with a clergy to the flagship and hieromonks to other ships.

The scientific part of the expedition was entrusted to Academician Peter Simon Pallas, promoted on December 31, 1786 to the rank of historiographer of the Russian fleet with a salary of 750 rubles. in year. For "maintaining a detailed travel journal with a clean calm" secretary Stepanov, who studied at Moscow and English universities, was invited. The scientific detachment of the expedition also included astronomer William Bailey, a member of Cook's voyage, naturalist Georg Forster, botanist Sommering and four painters. In England, it was planned to purchase astronomical and physical instruments: Godley's sextants, Arnold's chronometers, quadrants, telescopes, thermo- and barometers, for which Pallas entered into correspondence with the Greenwich astronomer Meskelin.

The library of the flagship included over fifty titles, among which were: “Description of the Land of Kamchatka” by S. P. Krasheninnikov, “General History of Travels” by Prevost Laharpe in twenty-three parts, the works of Engel and Dugald, extracts and copies of all journals of Russian voyages in the Eastern Ocean from 1724 to 1779, atlases and maps, including the “General Map, which presents convenient ways to increase Russian trade and navigation in the Pacific and Southern Oceans"Composed by Soymonov.

The expedition was prepared very carefully. A month after the decree, on April 17, the crews of the ships were assembled, all the officers moved to Kronstadt. The ships were raised on the stocks, work on them was in full swing until dark. Food was delivered to the ships: cabbage, 200 pounds for each salted sorrel, 20 pounds for dried horseradish, 25 pounds for onions and garlic. From Arkhangelsk, 600 pounds of cloudberries were delivered by special order, 30 barrels of sugar syrup, more than 1000 buckets of sbitnya, 888 buckets of double beer, etc. It was decided to buy meat, butter, vinegar, cheese in England. In addition to double uniform ammunition, the lower ranks and servants relied on twelve shirts and ten pairs of stockings (eight wool and two thread).

“To approve the Russian right to everything hitherto committed by Russian navigators, or newly made discoveries,” 200 cast-iron coats of arms were made, which were ordered to be strengthened on large pillars or “along the cliffs, hollowing out a nest”, 1700 gold, silver and cast-iron medals with inscriptions in Russian and Latin, which should have been buried in "decent places".

The expedition was well armed: 90 cannons, 197 jaegers, 61 hunting rifles, 24 fittings, 61 blunderbuss, 61 pistols and 40 officers' swords. The use of weapons was allowed only for protection Russian rights, but not to the natives of the newly acquired lands: “... there should be the first effort to sow in them a good idea about the Russians ... It is highly forbidden for you to use not only violence, but even for any brutal acts of revenge on the part.”

But with regard to foreign aliens, it was instructed to force them “by right, before the discoveries made to the Russian state, belonging to the places, to leave as soon as possible and henceforth neither about settlements, nor about auctions, nor about navigation; and if there are any fortifications or settlements, then you have the right to destroy, and to tear down and destroy signs and emblems. You should do the same with the ships of these aliens, in those waters, harbors or on the islands you will meet those who are able for similar attempts, forcing them to leave from there for the same reason. In the case of resistance, or, rather, strengthening, by using the force of arms, since your ships are so well armed to this end.

On October 4, 1787, the ships of the Mulovsky expedition, in full readiness for sailing, stretched out on the Kronstadt roadstead. The Russian minister-ambassador in England had already ordered pilots, who were waiting for the squadron in Copenhagen to escort it to Portsmouth.

But an urgent dispatch from Constantinople about the beginning of the war with Turkey crossed out all plans and works. The highest command followed: “The expedition being prepared for a long journey under the command of Captain Mulovsky’s fleet, under the present circumstances, should be postponed, and both officers, sailors and other people assigned to this squadron, as well as ships and various supplies prepared for it, should be turned into the number of that part fleet of ours, which, according to our decree of the 20th of this month, the Admiralty Board given, should be sent to the Mediterranean Sea.

But Mulovsky did not go to the Mediterranean either: the war with Sweden began, and he was appointed commander of the Mstislav frigate, where the young midshipman Ivan Kruzenshtern served under his command, who was destined to lead the first Russian circumnavigation in fifteen years. Mulovsky distinguished himself in the famous Battle of Gogland, for which on April 14, 1789 he was promoted to captain of the brigadier rank. Kireevsky and Trubetskoy received the same rank during the Russian-Swedish war. Three months later, on July 18, 1789, Mulovsky died in a battle near the island of Eland. His death and the outbreak of the French Revolution dramatically changed the situation. The resumption of circumnavigation was forgotten for a decade.

The first Russian circumnavigation of the world under the command of Ivan Fedorovich (Adam-Johann-Friedrich) Krusenstern (1803–1806)

The organization of the first, finally held, Russian circumnavigation is associated with the name of Ivan Fedorovich (Adam-Johann-Friedrich) Krusenstern. In 1788, when "due to a lack of officers" it was decided to prematurely release the midshipmen of the Naval Corps, who at least once went to sea, Kruzenshtern and his friend Yuri Lisyansky ended up serving in the Baltic. Taking advantage of the fact that Kruzenshtern served on the Mstislav frigate under the command of G. I. Mulovsky, they asked him to allow them to take part in a round-the-world voyage after the end of the war and received consent. After the death of Mulovsky, they began to forget about swimming, but Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky continued to dream about it. As part of a group of Russian naval officers, they were sent to England in 1793 to get acquainted with the experience of foreign fleets and gain practical skills in sailing across the expanses of the ocean. Krusenshern spent about a year in India, sailed to Canton, lived for six months in Macau, where he got acquainted with the state of trade in the Pacific Ocean. He drew attention to the fact that foreigners brought furs to Canton by sea, while Russian furs were delivered by land.

During the absence of Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky in Russia in 1797, the American United Company arose, in 1799 it was renamed the Russian-American Company (RAC). The imperial family was also a shareholder of RAK. Therefore, the company received the monopoly right to exploit the wealth of Russian possessions on the Pacific coast, trade with neighboring countries, build fortifications, maintain military forces, and build a fleet. The government entrusted her with the task of further expanding and strengthening Russian possessions in the Pacific. But the main problem of the RAC was the difficulty in delivering cargo and goods to Kamchatka and Russian America. The overland route through Siberia took up to two years and was costly. Cargoes often arrived spoiled, products were fabulously expensive, and equipment for ships (ropes, anchors, etc.) had to be divided into parts, and spliced and joined on the spot. Valuable furs mined in the Aleutian Islands often ended up in St. Petersburg spoiled and sold at a loss. Trade with China, where there was a great demand for furs, went through Kyakhta, where furs got from Russian America through Petropavlovsk, Okhotsk, Yakutsk. In terms of quality, the furs brought to the Asian markets in this way were inferior to the furs delivered to Canton and Macau by American and British ships in an immeasurably shorter time.

Upon his return to Russia, Kruzenshtern submitted two memorandums to Paul I justifying the need to organize round-the-world voyages. Kruzenshtern also suggested new order training of maritime personnel for merchant ships. To the six hundred cadets of the Naval Corps, he proposed to add another hundred people from other classes, mainly from ship's cabin boys, who would study together with noble cadets, but would be assigned to serve on commercial ships. The project was not accepted.

With the coming to power of Alexander I in 1801, the leadership of the College of Commerce and the Naval Ministry (the former Admiralty College) changed. On January 1, 1802, Kruzenshtern sent a letter to N. S. Mordvinov, vice-president of the Admiralty College. In it, he proposed his plan for circumnavigating the world. Kruzenshtern showed measures to improve the position of Russian trade on international market, protection of Russian possessions in North America, providing them and the Russian Far East with everything necessary. Much attention in this letter is paid to the need to improve the situation of the inhabitants of Kamchatka. Kruzenshtern's letter was also sent to the Minister of Commerce and the Director of Water Communications and the Commission for the Construction of Roads in Russia, Count Nikolai Petrovich Rumyantsev. The head of the RAC, Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov, also became interested in the project. Rezanov's petition was supported by Mordvinov and Rumyantsev.

In July 1802, it was decided to send two ships around the world. The official purpose of the expedition was to deliver the Russian embassy to Japan, headed by N.P. Rezanov. The costs of organizing this voyage were covered jointly by the RAC and the government. On August 7, 1802, I.F. Kruzenshtern was appointed head of the expedition. Its main tasks were defined: delivery of the first Russian embassy to Japan; delivery of provisions and equipment to Petropavlovsk and Novo-Arkhangelsk; geographical surveys along the route; inventory of Sakhalin, the estuary and the mouth of the Amur.

I. F. Kruzenshtern believed that a successful voyage would raise Russia's prestige in the world. But new head Naval Ministry P. V. Chichagov did not believe in the success of the expedition and offered to sail on foreign ships with hired foreign sailors. He ensured that the ships of the expedition were bought in England, and not built at Russian shipyards, as suggested by Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky. To purchase ships, Lisyansky was sent to England, he bought two sloops with a displacement of 450 and 370 tons for 17 thousand pounds and spent another 5 thousand on their repair. In June 1803 the ships arrived in Russia.

departure

And then came the historic moment. On July 26, 1803, the sloop “Nadezhda” and “Neva” left Kronstadt under the general leadership of I.F. Krusenshern. They were supposed to go around South America and reach the Hawaiian Islands. Then their paths diverged for a while. The task of "Nadezhda" under the command of Kruzenshtern included the delivery of goods to the Peter and Paul Harbor and then sending the mission of N.P. Rezanov to Japan, as well as the exploration of Sakhalin. The Neva, under the leadership of Yu. F. Lisyansky, was supposed to go with cargo to Russian America. The arrival of a warship here was to demonstrate the determination of the Russian government to protect the acquisitions of many generations of its sailors, merchants and industrialists. Then both ships were to be loaded with furs and set off for Canton, from where they, after passing the Indian Ocean and rounding Africa, were to return to Kronstadt and complete their circumnavigation there. This plan has been fully implemented.

Crews

The commanders of both ships put a lot of effort into turning a long voyage into a school for officers and sailors. Among the officers of Nadezhda there were many experienced sailors who later glorified the Russian fleet: the future admirals Makar Ivanovich Ratmanov and the discoverer of Antarctica Faddey Faddeevich Belingshausen, the future leader of two round-the-world voyages (1815-1818 and 1823-1826) Otto Evstafievich Kotzebue and his brother Moritz Kotzebue, Fyodor Romberg, Pyotr Golovachev, Ermolai Levenshtern, Philip Kamenshchikov, Vasily Spolokhov, artillery officer Alexei Raevsky and others. In addition to them, the crew of the Nadezhda included Dr. Karl Espenberg, his assistant Ivan Sidgam, astronomer I.K. Horner, naturalists Wilhelm Tilesius von Tilenau, Georg Langsdorf. Major Yermolai Fredericy, Count Fyodor Tolstoy, court adviser Fyodor Fos, painter Stepan Kurlyandtsev, physician and botanist Brinkin were present in the retinue of chamberlain N.P. Rezanov.

On the Neva were officers Pavel Arbuzov, Pyotr Povalishin, Fedor Kovedyaev, Vasily Berkh (later a historian of the Russian fleet), Danilo Kalinin, Fedul Maltsev, Dr. Moritz Liebend, his assistant Alexei Mutovkin, RAC clerk Nikolai Korobitsyn and others. In total, 129 people participated in the voyage. Kruzenshtern, who sailed for six years on English ships, notes: “I was advised to accept several foreign sailors, but, knowing the predominant properties of Russian ones, whom I even prefer to English ones, I did not agree to follow this advice.”

Academician Kruzenshtern

Shortly before leaving, on April 25, 1803, Krusenstern was elected a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences. Prominent scientists of the Academy took part in the development of instructions for various branches of scientific research. The ships were equipped with the best nautical instruments and aids for those times, as well as the latest scientific instruments.

"Hope" in Kamchatka...

Rounding Cape Horn, the ships parted. After conducting research in the Pacific Ocean, the Nadezhda arrived in Petropavlovsk on July 3, 1804, and the Neva arrived on July 1 in Pavlovsk Harbor on Kodiak Island.

The stay in Petropavlovsk was delayed: they were waiting for the head of Kamchatka, Major General P.I. Koshelev, who was in Nizhnekamchatsk. The Petropavlovsk commandant, Major Krupsky, provided the crew with all possible assistance. “The ship was equipped immediately, and everything was taken to the shore, from which we stood no further than fifty fathoms. Everything belonging to the ship's equipment, after such a long voyage, required either correction or change. Supplies and goods loaded in Kronstadt for Kamchatka were also unloaded,” writes Kruzenshtern. Finally, General Koshelev arrived from Nizhnekamchatsk with his adjutant, younger brother Lieutenant Koshelev, Captain Fedorov and sixty soldiers. In Petropavlovsk, there were changes in the composition of the embassy of N.P. Rezanov to Japan. Lieutenant Tolstoy, Dr. Brinkin and the painter Kurlyandtsev went to Petersburg by land. The embassy included the captain of the Kamchatka garrison battalion Fedorov, lieutenant Koshelev and eight soldiers. In Kamchatka, the Japanese Kiselev, the interpreter (translator) of the embassy, and the “wild Frenchman” Joseph Kabrit, whom the Russians found on the island of Nukagiva in the Pacific Ocean, remained in Kamchatka.

…And in Japan

After repairs and replenishment of supplies, on August 27, 1804, Nadezhda set off with the embassy of N.P. Rezanov to Japan, where she stood in the port of Nagasaki for more than six months. April 5, 1805 "Hope" left Nagasaki. On the way to Kamchatka, she described the southern and eastern coasts of Sakhalin. On May 23, 1805, the Nadezhda again arrived in Petropavlovsk, where N.P. Rezanov and his retinue left the ship and on the RAC ship St. Maria" went to Russian America on Kodiak Island. The results of Rezanov's voyage to Japan were reported by the head of Kamchatka, P.I. Koshelev, to the Siberian governor Selifontov.

From June 23 to August 19, Kruzenshtern sailed in the Sea of Okhotsk, off the coast of Sakhalin, in the Sakhalin Bay, where he carried out hydrographic work and, in particular, studied the estuary of the Amur River - he was engaged in solving the "Amur issue". September 23, 1805 "Nadezhda" finally left Kamchatka and with a cargo of furs went to Macau, where she was supposed to meet with the "Neva" and, loaded with tea, return to Kronstadt. They left Macau on January 30, 1806, but the ships parted at the Cape of Good Hope. The Neva arrived in Kronstadt on July 22, and the Nadezhda arrived on August 7, 1806. Thus ended the first round-the-world voyage of Russian sailors.

Geographic discoveries (and misconceptions)

It was marked by significant scientific results. Both ships carried out continuous meteorological and oceanological observations. Kruzenshtern described: the southern shores of the Nukagiva and Kyushu islands, the Van Diemen Strait, the islands of Tsushima, Goto and a number of others adjacent to Japan, the northwestern shores of the islands of Honshu and Hokkaido, as well as the entrance to the Sangar Strait. Sakhalin was put on the map almost along its entire length. But Kruzenshtern failed to complete his research in the Amur estuary, and he made an incorrect conclusion about the peninsular position of Sakhalin, extending the erroneous conclusion of La Perouse and Broughton for forty-four years. Only in 1849, G. I. Nevelskoy established that Sakhalin is an island.

Conclusion

Krusenstern left an excellent description of his voyage, the first part of which was published in 1809, and the second in 1810. Soon it was reprinted in England, France, Italy, Holland, Denmark, Sweden and Germany. The description of the trip was accompanied by an atlas of maps and drawings, among which were the "Map of the North-Western Part of the Great Ocean" and "Map of the Kuril Islands". They were a significant contribution to the study of the geography of the northern part of the Pacific Ocean. Among the drawings made by Tilesius and Horner, there are views of the Peter and Paul harbor, Nagasaki and other places.

At the end of the voyage, Kruzenshtern received many honors and awards. So, in honor of the first Russian circumnavigation, a medal with his image was knocked out. In 1805, Kruzenshtern was awarded the Order of St. Anna and St. Vladimir of the third degree, received the rank of captain of the 2nd rank and a pension of 3,000 rubles a year. Until 1811, Krusenshern was engaged in the preparation and publication of a description of his journey, reports and calculations on the expedition. Officially, he was in 1807-1809. was listed at the Petersburg port. In 1808 he became an honorary member of the Admiralty Department, on March 1, 1809 he was promoted to captain of the 1st rank and appointed commander of the ship "Blagodat" in Kronstadt.

Since 1811, Kruzenshtern began his service in the Naval Cadet Corps as a class inspector. Here he served intermittently until 1841, becoming its director. On February 14, 1819, he was promoted to captain-commander, in 1823 he was appointed a permanent member of the Admiralty Department, and on August 9, 1824, he became a member of the Main Board of Schools. On January 8, 1826, with the rank of Rear Admiral Kruzenshtern, he was appointed assistant director of the Naval Cadet Corps, and from October 14 of the same year he became its director and held this post for fifteen years. He founded a library and a museum, created officer classes for the further education of the most capable midshipmen who graduated with honors from the corps (later these classes were transformed into the Naval Academy). In 1827 he became an indispensable member of the Scientific Committee of the Naval Staff and a member of the Admiralty Council, in 1829 he was promoted to vice admiral, and in 1841 he became a full admiral.

Through the mountains to the sea with a light backpack. Route 30 passes through the famous Fisht - this is one of the most grandiose and significant natural monuments in Russia, the closest to Moscow high mountains. Tourists travel lightly through all the landscape and climatic zones of the country from the foothills to the subtropics, spending the night in shelters.

Trekking in Crimea - 22 route

From Bakhchisarai to Yalta - there is no such density of tourist facilities as in the Bakhchisarai region anywhere in the world! Mountains and the sea, rare landscapes and cave cities, lakes and waterfalls, secrets of nature and mysteries of history, discoveries and the spirit of adventure are waiting for you... Mountain tourism here is not difficult at all, but any trail surprises.

Adygea, Crimea. Mountains, waterfalls, herbs of alpine meadows, healing mountain air, absolute silence, snowfields in the middle of summer, the murmur of mountain streams and rivers, stunning landscapes, songs around the fires, the spirit of romance and adventure, the wind of freedom are waiting for you! And at the end of the route, the gentle waves of the Black Sea.

Domestic navigators - explorers of the seas and oceans Zubov Nikolai Nikolaevich

2. Round-the-world voyage of Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky on the ships Nadezhda and Neva (1803–1806)

2. Round-the-world voyage of Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky on the ships "Nadezhda" and "Neva"

The main objectives of the first Russian round-the-world expedition of Kruzenshtern-Lisyansky were: the delivery of cargoes of the Russian-American company to the Far East and the sale of furs of this company in China, the delivery of an embassy to Japan, which had the goal of establishing trade relations with Japan, and the production of associated geographical discoveries and research.

For the expedition, two ships were bought in England: one with a displacement of 450 tons, called the Nadezhda, and another with a displacement of 350 tons, called the Neva. Lieutenant Commander Ivan Fedorovich Kruzenshtern took command of the Nadezhda, Lieutenant Commander Yuri Fedorovich Lisyansky took command of the Neva.

The crews of both ships, both officers and sailors, were military and recruited from volunteers. Krusenstern was advised to take several foreign sailors for the first round-the-world voyage. “But,” writes Kruzenshtern, “I, knowing the predominant properties of Russian, which I even prefer to English, did not agree to follow this advice.” Kruzenshtern never repented of this. On the contrary, after crossing the equator, he noted a remarkable property of a Russian person - it is equally easy to endure both the most severe cold and the burning heat.

71 people sailed on the Nadezhda and 53 people on the Neva. In addition, the astronomer Horner, the naturalists Tilesius and Langsdorf, and the doctor of medicine Laband participated in the expedition.

Despite the fact that Nadezhda and Neva belonged to a private Russian-American company, Alexander I allowed them to sail under a military flag.

All preparations for the expedition were carried out very carefully and lovingly. On the advice of G. A. Sarychev, the expedition was equipped with the most modern astronomical and navigational instruments, in particular chronometers and sextants.

Unexpectedly, just before setting sail, Kruzenshtern was given the task of taking to Japan Ambassador Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov, one of the main shareholders of the Russian-American Company, who was supposed to try to establish trade relations with Japan. Rezanov and his retinue fit on the Nadezhda. This task forced us to reconsider the work plan of the expedition and, as we will see later, resulted in the loss of time for the Nadezhda to sail to the shores of Japan and stop in Nagasaki.

The very intention of the Russian government to establish trade relations with Japan was quite natural. After the Russians entered the Pacific Ocean, Japan became one of Russia's closest neighbors. It has already been mentioned that even the Spanberg expedition was tasked with finding sea routes to Japan, and that the ships of Spanberg and Walton were already approaching the shores of Japan and conducted friendly barter with the Japanese.

It happened further that on the Aleutian island of Amchitka around 1782 a Japanese ship was wrecked and its crew was brought to Irkutsk, where they lived for almost 10 years. Catherine II ordered the Siberian governor-general to send the detained Japanese home and use this pretext to establish trade with Japan. Lieutenant Adam Kirillovich Laksman, elected as a representative for the negotiations of the guard, on the transport "Ekaterina" under the command of navigator Grigory Lovtsov, set off from Okhotsk in 1792 and spent the winter in the harbor of Nemuro on the eastern tip of the island of Hokkaido. In the summer of 1793, at the request of the Japanese, Laksman moved to the port of Hakodate, from where he traveled by land for negotiations to Matsmai, the main city of the island of Hokkaido. During the negotiations, Laxman, thanks to his diplomatic skill, was successful. In particular, paragraph 3 of the document received by Laxman stated:

“3. The Japanese cannot enter into negotiations on trade anywhere, except for the one designated for this port of Nagasaki, and therefore now they only give Laxman a written form with which one Russian ship can arrive at the aforementioned port, where Japanese officials will be located who will have to negotiate with the Russians on this subject. ". Having received this document, Laxman returned to Okhotsk in October 1793. Why this permission was not used immediately remains unknown. In any case, Nadezhda, together with Ambassador Rezanov, was supposed to go to Nagasaki.

During the stay in Copenhagen (August 5-27) and in another Danish port, Helsingør (August 27-September 3), cargoes were carefully shifted on the Nadezhda and on the Neva and the chronometers were checked. The scientists Horner, Tilesius and Langsdorf invited to the expedition arrived in Copenhagen. On the way to Falmouth (southwestern England), during a storm, the ships parted and the Neva arrived there on September 14, and the Nadezhda on September 16.

Nadezhda and Neva left Falmouth on September 26 and on October 8 anchored in Santa Cruz Bay on the island of Tenerife (Canary Islands), where they stayed until October 15.

November 14, 1803 "Nadezhda" and "Neva" for the first time in the history of the Russian fleet crossed the equator. Of all the officers and sailors, only the commanders of the ships, who had previously sailed as volunteers in the English fleet, crossed it before. Who would have thought then that seventeen years later the Russian warships Vostok and Mirny, making a round-the-world voyage in high southern latitudes, would discover what the sailors of other nations failed to do - the sixth continent of the globe - Antarctica!

On December 9, the ships arrived at the island of St. Catherine (off the coast of Brazil) and stayed here until January 23, 1804, to change the fore and main masts on the Neva.

Rounding Cape Horn, the ships parted on March 12 during a storm. In this case, Kruzenshtern appointed successive meeting places in advance: Easter Island and the Marquesas Islands. However, on the way, Krusenstern changed his mind, went straight to the Marquesas Islands, and on April 25 anchored off the island of Nuku Hiva.

Lisyansky, unaware of such a change in route, went to Easter Island, stayed with him under sail from April 4 to April 9, and, without waiting for Kruzenshtern, went to the island of Nuku-Khiva, where he arrived on April 27.

The ships stayed off the island of Nuku Hiva until May 7. During this time, a convenient anchorage was found and described, called the port of Chichagov, and the latitudes and longitudes of several islands and points were determined.

From the island of Nuku Hiva, the ships went north and on May 27 approached the Hawaiian Islands. Purchase Kruzenshtern's calculations from local residents fresh provisions were unsuccessful. Kruzenshtern stayed off the Hawaiian Islands under sail on May 27 and 28, and then, in order not to delay his task of visiting Nagasaki, he went straight to Petropavlovsk, where he arrived on July 3. Lisyansky, anchored off the island of Hawaii from May 31 to June 3, went according to plan to Kodiak Island.

From Petropavlovsk, Krusenstern went to sea on August 27, went south along the eastern coast of Japan and then through the Vandimen Strait (south of Kyushu) from the Pacific Ocean to the East China Sea. September 26 "Hope" anchored in Nagasaki.

Rezanov's embassy was unsuccessful. The Japanese not only did not agree to any treaty with Russia, but did not even accept gifts intended for the Japanese emperor.

On April 5, 1805, Krusenstern, finally leaving Nagasaki, passed through the Korea Strait, ascended the Sea of Japan, which was then almost unknown to Europeans, and put on the map many notable points of the western coast of Japan. The position of some points was determined astronomically.

On May 1, Kruzenshtern passed through the La Perouse Strait from the Sea of Japan to the Sea of Okhotsk, carried out some hydrographic work here, and on May 23, 1805, returned to Petropavlovsk, where Rezanov's embassy left Nadezhda.

Round-the-world voyage of Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky on the "Nadezhda" and "Neva" (1803-1806).

On September 23, 1805, Nadezhda, after reloading the holds and replenishing provisions, left Petropavlovsk on the return voyage to Kronstadt. Through the Bashi Strait, she proceeded to the South China Sea and on November 8 anchored in Macau.

"Neva" after parking at the Hawaiian Islands went, as already mentioned, to the Aleutian Islands. On June 26, Chirikov Island was opened, and on July 1, 1804, the Neva anchored in Pavlovskaya Harbor of Kodiak Island.

Having fulfilled the instructions given to him, having performed some hydrographic work off the coast of Russian America and having received the furs of the Russian-American Company, Lisyansky on August 15, 1805 left Novo-Arkhangelsk also for Macau, as was previously agreed with Kruzenshtern. From Russian America, he took with him three Creole boys (Russian father, Aleut mother) in order for them to receive in Russia special education, and then returned to Russian America.

October 3 on the way to Canton, in the northern subtropical Pacific Ocean, we saw a lot of birds. Assuming that some unknown land was nearby, proper precautions were taken. However, in the evening, the Neva still ran aground. At dawn we saw that the Neva was near a small island. Soon it was possible to get off the shallows, but the Neva was again struck by a squall on the stones. Refloating, raising the cannons thrown into the sea with floats to lighten the ship, delayed the Neva in this area until October 7th. The island in honor of the commander of the ship was named Lisyansky Island, and the reef on which the Neva was sitting was the Neva reef.

On the way to Canton, the Neva withstood a severe typhoon, during which it received some damage. A significant amount of fur goods was soaked and then thrown overboard.

On November 16, rounding the island of Formosa from the south, the Neva entered the South China Sea and on November 21 anchored in Macau, where the Nadezhda was already anchored at that time.

The sale of furs delayed the Nadezhda and the Neva, and only on January 31, 1806 did both ships leave Chinese waters. Subsequently, the ships passed through the Sunda Strait and on February 21 entered the Indian Ocean.

On April 3, being almost at the Cape of Good Hope, in cloudy weather with rain, the ships parted.

As Kruzenshtern writes, “on April 26 (April 14, old st. N. 3.) we saw two ships, one on NW, and the other on NO. We recognized the first one as the Neva, but as the Nadezhda went worse, the Neva soon fell out of sight again, and we didn’t see it until our arrival in Kronstadt.

Kruzenshtern appointed the island of St. Helena as a meeting place in case of separation, where he arrived on April 21. Here Kruzenshtern learned about the break in relations between Russia and France, and therefore, having left the island on April 26, in order to avoid meeting with enemy cruisers, he chose the path to the Baltic Sea not through the English Channel, but to the north of the British Isles. On July 18-20, Nadezhda was anchored in Helsingør and on July 21-25 in Copenhagen. On August 7, 1806, after an absence of 1,108 days, Nadezhda returned to Kronstadt. During the voyage, Nadezhda spent 445 days under sail. The longest passage from St. Helena to Helsingør lasted 83 days.

The Neva, after parting with the Nadezhda, did not go to St. Helena, but went straight to Portsmouth, where she stood from June 16 to July 1. Having stopped for a short time on the roadstead of the Downs and in Helsingor, the Neva arrived in Kronstadt on July 22, 1806, having spent 1090 days in the absence, of which 462 days were under sail. The longest was the passage from Macau to Portsmouth, it lasted 142 days. No other Russian ship made such a long sailing trip.

The health of the crews on both ships was excellent. During the three-year voyage on the Nadezhda, only two people died: the envoy's cook, who was ill with tuberculosis even when he entered the ship, and Lieutenant Golovachev, who shot himself for an unknown reason while staying off St. Helena. On the Neva, one sailor fell into the sea and drowned, three people were killed during a military skirmish near Novo-Arkhangelsk, and two sailors died of accidental illnesses.

The first Russian circumnavigation was marked by significant geographical results. Both ships, both in a joint voyage and in a separate one, all the time tried to arrange their courses either in such a way as to pass along the still “untrodden” paths, or in such a way as to pass to the dubious islands shown on old maps.

There were many such islands in the Pacific Ocean at that time. They were charted by brave sailors who used poor navigational tools and poor methods. It is not surprising, therefore, that the same island was sometimes discovered by many navigators, but placed under different names in different places on the map. Especially large were the errors in longitude, which on old ships was determined only by reckoning. So, for example, longitudes were determined during the voyage of Bering - Chirikov.

On "Nadezhda" and "Neva" there were sextants and chronometers. In addition, relatively shortly before their voyage, a method was developed for determining longitude on ships from the angular distances of the Moon from the Sun (in other words, the “method of lunar distances”). This greatly facilitated the determination of latitudes and longitudes at sea. And on the "Nadezhda" and on the "Neva" they did not miss a single opportunity to determine their coordinates. So, during the voyage of the Nadezhda in the Sea of Japan and the Sea of Okhotsk, the number of points determined astronomically was more than a hundred. Frequent determinations of the geographical coordinates of points visited or seen by the expedition members are a great contribution to geographical science.

Due to the accuracy of their calculation, based on frequent and accurate determinations of latitudes and longitudes, both ships were able to determine the directions and speeds of sea currents in many areas of their navigation by the difference between the numbered and observed places.

The accuracy of the reckoning on the "Nadezhda" and "Neva" allowed them to "remove from the map" many non-existent islands. Thus, upon leaving Petropavlovsk for Canton, Kruzenshtern arranged his courses with the expectation to follow the paths of the English captains Clerk and Gore and inspect the area between 33 and 37 ° N. sh. along the 146° east meridian. Near this meridian, several dubious islands were shown on their maps and on some others.

Lisyansky, on leaving Kodiak for Canton, arranged his courses in such a way as to cross the then almost unknown spaces of the Pacific Ocean and pass through the area in which the English captain Portlock in 1786 noticed signs of land and where he himself, on the way from the Hawaiian Islands to Kodiak, saw the sea otter. As we have seen, Lisyansky eventually succeeded, albeit much to the south, in discovering Lisyansky Island and the Kruzenshtern Reef.

Continuous and thorough meteorological and oceanological observations were carried out on both ships. On the Nadezhda, in addition to the usual measurements of the temperature of the surface layer of the ocean, the Six's thermometer, invented in 1782, was used for the first time for deep-sea research, designed to measure the highest and lowest temperatures. With the help of this thermometer, the vertical distribution of temperatures in the ocean was studied in seven places. In total, deep temperatures, down to a depth of 400 m, were determined in nine places. These were the first in the world practice to determine the vertical distribution of temperatures in the ocean.

Particular attention was paid to observations of the state of the sea. In particular, the bands and patches of the rough sea (rips) created at the meeting of sea currents were carefully described.

The glow of the sea was also noted, at that time still insufficiently explained. This phenomenon was studied on Nadezhda as follows: “... they took a cup, put several sawdust in it, covered it with a white thin, double-folded handkerchief, on which they immediately poured water scooped from the sea, and it turned out that many dots that glowed when the handkerchief was shaken; the filtered water did not give the slightest light ... Dr. Langsdorf, who tested these small luminous bodies through a microscope ... discovered that many ... were real animals ... "

Now it is known that the glow is created by the smallest organisms and is divided into constant, arbitrary and forced (under the influence of irritation). The latter is discussed in the description of Kruzenshtern.

The descriptions of the nature and life of the population of the areas visited by Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky are very interesting. Of particular value are the descriptions of the Nukukhivs, Hawaiians, Japanese, Aleuts, American Indians and inhabitants of the northern part of Sakhalin.

On the island of Nuku Hiva, Krusenstern spent only eleven days. Of course, for such short term about the inhabitants of this island, one could create only a cursory impression. But, fortunately, on this island, Kruzenshtern met an Englishman and a Frenchman who lived here for several years and, by the way, were at enmity with each other. From them, Kruzenshtern collected a lot of information, checking the stories of an Englishman by polling a Frenchman, and vice versa. In addition, the Frenchman left Nuku Khiva on the Nadezhda, and during the further voyage, Kruzenshtern had the opportunity to replenish his information. All sorts of collections, sketches, maps and plans brought by both courts deserve special attention.

Kruzenshtern, during his voyage in foreign waters, described: the southern coast of the island of Nuku-Hiva, the southern coast of the island of Kyushu and the Van Diemen Strait, the islands of Tsushima and Goto and a number of other islands adjacent to Japan, the northwestern coast of Honshu, the entrance to the Sangar Strait, and also the western coast of Hokkaido.

Lisyansky, while sailing in the Pacific Ocean, described Easter Island, discovered and put on the map Lisyansky Island and the reefs of the Neva and Kruzenshtern.

Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky were not only brave sailors and explorers, but also excellent writers who left us descriptions of their voyages.

In 1809–1812 Kruzenshtern's work "Traveling around the world in 1803, 1804, 1805 and 1806 on the ships" Nadezhda "and" Neva "in three volumes with an album of drawings and an atlas of maps" was published.

The books of Kruzenshtern and Lisyansky were translated into foreign languages and for a long time served as navigation aids for ships sailing in the Pacific Ocean. Written on the model of Sarychev's books, they, in terms of content and form, in turn, served as a model for all books written by Russian navigators of the subsequent time.

It should be emphasized once again that the voyages of the Nadezhda and the Neva pursued purely practical goals - scientific observations were made only along the way. Nevertheless, the observations of Krusenstern and Lisyansky would do credit to many purely scientific expeditions.

It is necessary to say a few words about some of the malfunctions, which, unfortunately, somewhat overshadow the brilliant first voyage of Russian sailors around the world from a purely maritime point of view.

The fact is that it was not by chance that two ships were sent to this expedition. Just as in the organization of the sea expeditions of Bering - Chirikov and Billings - Sarychev, it was believed that the ships, sailing together, could always help each other in case of need.

According to the instructions, the separate voyage of the Nadezhda and the Neva was allowed only for the duration of the Nadezhda's visit to Japan. This was justified by the fact that Japan, according to the previous agreement, allowed only one Russian ship to enter Japan. What actually happened?

During a storm near Cape Horn, the Nadezhda and the Neva parted ways. Kruzenshtern did not go to the agreed in advance, in case of separation, meeting place - Easter Island, but went straight to the second agreed meeting point - the Marquesas Islands, where the ships met and went on together to the Hawaiian Islands. From the Hawaiian Islands, the ships went again separately, performing various tasks. The ships met again only in Macau, from where they went together to the Indian Ocean. Not far from Africa, the ships again lost sight of each other during a storm. In such a case, the island of St. Helena was appointed as the meeting place, where the Nadezhda entered. Lisyansky, carried away by the record for the duration of sailing, went straight to England. Kruzenshtern was wrong in not going to Easter Island, as was due. Lisyansky was also wrong in not going to St. Helena. References to separations due to the storm are not very convincing. Storms and fogs off the coast of Antarctica are no less frequent and strong than in the Indian Ocean, and meanwhile, as we shall see later, the ships of Bellingshausen and Lazarev never parted while rounding Antarctica.

From the book Pirates of the British Crown Francis Drake and William Dampier author Malakhovskiy Kim VladimirovichChapter Five The last circumnavigation of the world Enter into a share with Goldney, who contributed about 4 thousand pounds. Art. in a new enterprise, there were many willing from the most famous families of Bristol. Among them were merchants, and lawyers, and the alderman of Bristol Batchelor himself. I contributed my share and

From the book Domestic Navigators - Explorers of the Seas and Oceans author Zubov Nikolai Nikolaevich6. Golovnin's circumnavigation on the sloop "Kamchatka" (1817-1819) In 1816, it was decided to send a warship to the Far East with the following tasks: different materials and supplies to the ports of Petropavlovsk and Okhotsk, 2) to examine the state of affairs of the Russian-American company

From the book Three trips around the world author Lazarev Mikhail Petrovich11. Round-the-world voyage of M. Lazarev on the frigate "Cruiser" (1822-1825) and the voyage of Andrei Lazarev on the sloop "Ladoga" to Russian America (1822-1823) 36-gun frigate "Cruiser" under the command of Captain 2nd Rank Mikhail Petrovich Lazarev and the 20-gun sloop Ladoga, which

From the book The first Russian voyage around the world author Kruzenshtern Ivan Fyodorovich13. Kotzebue circumnavigating the world on the sloop "Enterprise" (1823–1826) The sloop "Enterprise" under the command of Lieutenant Commander Otto Evstafievich Kotzebue was entrusted with the delivery of goods to Kamchatka and cruising to protect Russian settlements on the Aleutian Islands. At the same time

From the book Notes of a sailor. 1803–1819 author Unkovsky Semyon Yakovlevich14. Wrangel's round-the-world voyage on the Krotkiy transport (1825–1827) The Krotkiy military transport (90 feet long) specially built for the upcoming voyage under the command of Lieutenant Commander Ferdinand Petrovich Wrangel, who had already completed a round-the-world voyage

From the author's book15. Stanyukovich's round-the-world voyage on the sloop Moller (1826-1829) Following the example of the previous round-the-world voyages, in 1826 it was decided to send two warships from Kronstadt to protect the fisheries in Russian America and to deliver cargo to the port of Peter and Paul. But

From the author's book16. Litke's circumnavigation of the world on the Senyavin sloop (1826–1829) The commander of the Senyavin sloop, which went on a joint circumnavigation with the Moller sloop, Lieutenant Commander Fyodor Petrovich Litke circumnavigated the world as a midshipman on the Kamchatka in 1817–1819 years. Then

From the author's book17. Gagemeister's round-the-world voyage on the Krotkiy transport (1828–1830) The military transport Krotkiy, which returned from a round-the-world voyage in 1827, was again sent in 1828 with cargoes for Petropavlovsk and Novo-Arkhangelsk. It was commanded by Lieutenant Commander

From the author's book19. Shants' circumnavigation on the transport "America" (1834–1836) The military transport "America", which returned in 1833 from the circumnavigation and was somewhat redesigned, on August 5, 1834, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Ivan Ivanovich Shants, again left Kronstadt with loads

From the author's book20. Juncker's circumnavigation on the transport "Abo" (1840-1842) The military transport "Abo" (128 feet long, with a displacement of 800 tons) under the command of Lieutenant Commander Andrei Logginovich Junker left Kronstadt on September 5, 1840. Going to Copenhagen, Helsingor, Portsmouth, to the island

From the author's book2. Kruzenshtern's voyage on the ship "Nadezhda" in the Sea of Okhotsk (1805) The ship of the Russian-American company - "Nadezhda" under the command of Lieutenant Commander Ivan Fedorovich Kruzenshtern arrived in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky on July 3, 1804. Overloaded and restocked

From the author's book3. Lisyansky's voyage on the ship "Neva" in the waters of Russian America (1804-1805) The ship of the Russian-American company "Neva" under the command of Lieutenant Commander Yuri Fedorovich Lisyansky, leaving Kronstadt together with the "Nadezhda" on July 26, 1803, came to Pavlovsk harbor of the island

From the author's bookM. P. LAZAREV’S AROUND THE WORLD VOYAGE ON THE VESSEL “SUVOROV”

From the author's book From the author's bookJOURNEY AROUND THE WORLD IN 1803, 1804, 1805 AND 1806 ON THE SHIPS "NOPE" AND "NEVA" observations were made

August 17, 1806 - the sloop "Neva" under the command of Yuri Lisyansky anchored in the Kronstadt roadstead, completing the first Russian circumnavigation, which lasted a little over three years. By order of Alexander I, a special medal was issued for all participants in the journey.

On August 7, 1803, two ships set out on a long voyage from Kronstadt. These were the ships "Nadezhda" and "Neva", on which Russian sailors were to make a round-the-world trip.

Ivan Fyodorovich Kruzenshtern

Kruzenshtern project

The head of the expedition was Captain-Lieutenant Ivan Fedorovich Kruzenshtern, the commander of the Nadezhda. The Neva was commanded by Lieutenant Commander Yuri Fedorovich Lisyansky. Both were experienced sailors who had already taken part in long-distance voyages. Kruzenshtern improved in maritime affairs in England, took part in Anglo-French War, was in America, India, China. During his travels, Kruzenshtern came up with a bold project, the implementation of which was intended to promote the expansion of Russian trade relations with China. It consisted in the fact that instead of a difficult and long journey by land, to establish communication with the American possessions of the Russians (Alaska) by sea. On the other hand, Kruzenshtern suggested a closer point for selling furs, namely China, where furs were in great demand and were valued very dearly. To implement the project, it was necessary to undertake a long journey and explore this new path for the Russians.

After reading Kruzenshtern's draft, Paul I muttered: "What nonsense!" - and that was enough for a bold undertaking to be buried for several years in the affairs of the Naval Department. Under Alexander I, Krusenstern again began to achieve his goal. He was helped by the fact that Alexander himself had shares in the Russian-American Company. The travel plan has been approved.

preparations

It was necessary to purchase ships, since there were no ships suitable for long-distance navigation in Russia. The ships were bought in London. Kruzenshtern knew that the trip would give a lot of new things for science, so he invited several scientists and the painter Kurlyandtsev to participate in the expedition.

The expedition was comparatively well equipped with precise instruments for conducting various observations, had a large collection of books, nautical charts and other manuals necessary for long-distance navigation.

Kruzenshtern was advised to take English sailors on the voyage, but he protested vigorously, and the Russian team was recruited. Krusenstern paid special attention to the preparation and equipment of the expedition. Both equipment for sailors and individual, mainly antiscorbutic, food products were purchased by Lisyansky in England.

Map of the first Russian round-the-world trip

Having approved the expedition, the king decided to use it to send an ambassador to Japan. The embassy had to repeat the attempt to establish relations with Japan, which at that time was almost completely unknown to the Russians. Japan traded only with Holland, for other countries its ports remained closed. In addition to gifts to the Japanese emperor, the embassy mission was supposed to take home several Japanese who accidentally ended up in Russia after a shipwreck and lived there for quite a long time.

Sailing to Cape Horn.

The first stop was in Copenhagen, where instruments were checked at the observatory. Departing from the coast of Denmark, the ships headed for the English port of Falmouth. While staying in England, the expedition acquired additional astronomical instruments.

Yuri Fedorovich Lisyansky

From England ships headed south along the east coast Atlantic Ocean. October 20 "Nadezhda" and "Neva" were on the roadstead of the small Spanish city of Santa Cruz, located on the island of Tenerife. The expedition stocked up on food, fresh water, and wine. Sailors, walking around the city, saw the poverty of the population and witnessed the arbitrariness of the Inquisition. In his notes, Kruzenshtern noted: “It is terrible for a free-thinking person to live in such a world where the anger of the Inquisition and the unlimited autocracy of the governor operate in full force, disposing of the life and death of every citizen.”

Leaving Tenerife, the expedition headed for the shores South America. During the voyage, scientists conducted a study of the temperature of different layers of water. An interesting phenomenon was noticed, the so-called "glow of the sea". A member of the expedition, the naturalist Tilesius established that the light was given by the smallest organisms, which were in abundance in the water. Carefully filtered water ceased to glow.

On November 23, 1803, the ships crossed the equator, and on December 21 they entered the Portuguese possessions, which at that time included Brazil, and anchored off Catherine Island. The mast needed to be repaired. The stop made it possible to conduct astronomical observations in the observatory installed on the shore. Kruzenshtern notes the great natural wealth of the region, in particular, tree species. It has up to 80 samples of valuable tree species that could be traded. Off the coast of Brazil, observations were made of the tides, the direction of sea currents, and water temperatures at various depths.

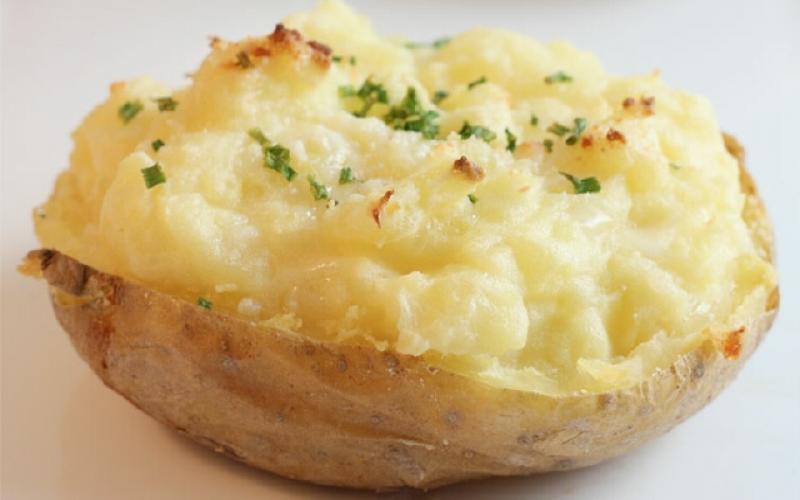

Sloop "Hope" off the coast of South America

To the shores of Kamchatka and Japan

Near Cape Horn, due to stormy weather, the ships were forced to separate. The meeting point was set at Easter Island or Nukagiva Island. Safely rounding Cape Horn, Kruzenshtern headed for Nukagiva Island and anchored in the port of Anna Maria. The sailors met two Europeans on the island - an Englishman and a Frenchman, who lived with the islanders for several years. The islanders brought coconuts, breadfruit and bananas in exchange for old metal hoops. Russian sailors visited the island. Krusenstern gives a description appearance islanders, their tattoos, jewelry, dwellings, dwells on the characteristics of life and public relations. The Neva came to Nukagiva Island late, as Lisyansky was looking for the Nadezhda near Easter Island. Lisyansky also reports a number of interesting information about the population of Easter Island, the clothes of the inhabitants, dwellings, gives a description of the wonderful monuments erected on the shore, which La Perouse mentioned in his notes.

After sailing from the shores of The Nukagiva expedition headed for the Hawaiian Islands. There, Kruzenshtern planned to stock up on food, especially fresh meat, which the sailors had not had for a long time. However, what Krusenstern offered to the islanders in exchange did not satisfy them, since the ships that landed on the Hawaiian Islands often brought European goods here.

The Hawaiian Islands were the point of travel where the ships had to separate. From here, the path of the Nadezhda went to Kamchatka and then to Japan, and the Neva was supposed to follow to the northwestern shores of America. The meeting was scheduled in China, in the small Portuguese port of Macau, where the purchased furs were to be sold. The ships parted.

Sloop "Hope"

July 14, 1804 "Nadezhda" entered the Avacha Bay and anchored off the city of Petropavlovsk. In Petropavlovsk, the goods brought for Kamchatka were unloaded, and the ship's gear, which had worn out during a long journey, was repaired. In Kamchatka, the main food of the expedition was fresh fish, which, however, could not be stocked up for further sailing due to the high cost and lack of the required amount of salt.

On August 30, Nadezhda left Petropavlovsk and headed for Japan. Almost a month has passed in swimming. On September 28, the sailors saw the shores of the island of Kiu-Siu (Kyu-Su). Heading to the port of Nagasaki, Kruzenshtern explored the Japanese coast, which has many bays and islands. He was able to establish that on the sea charts of that time, in a number of cases, the shores of Yaponka were plotted incorrectly.

Dropping anchor in Nagasaki, Kruzenshtern informed the local governor of the arrival of the Russian ambassador. However, the sailors were not allowed to go ashore. The issue of receiving the ambassador was to be decided by the emperor himself, who lived in Ieddo, so he had to wait. Only after 1.5 months, the governor allocated a certain place on the shore, surrounded by a fence, where the sailors could walk. Even later, after repeated appeals from Krusenstern, the governor set aside a house for the ambassador on the shore.

Only on March 30 did a representative of the emperor arrive in Nagasaki, who was instructed to negotiate with the ambassador. During the second meeting, the commissioner said that the Japanese emperor had refused to sign a trade treaty with Russia and that Russian ships were not allowed to enter Japanese ports. The Japanese, brought to their homeland, nevertheless, finally got the opportunity to leave the Nadezhda.

Back to Petropavlovsk

From Japan, Nadezhda headed back to Kamchatka. Kruzenshtern decided to return by another route - along the western coast of Japan, almost unexplored at that time by Europeans. The Nadezhda sailed along the coast of Nipon Island (Hopshu), explored the Sangar Strait, and passed the western coast of Iesso Island (Hokkaido). Having reached the northern tip of Iesso, Kruzenshtern saw the Ainu, also living in the southern part of Sakhalin. In his notes, he gives a description of the physical appearance of the Ainu, their clothes, dwellings, occupations.

Following further, Kruzenshtern carefully explored the shores of Sakhalin. However, he was prevented from continuing his journey to the northern tip of Sakhalin by the accumulation of ice. Krusenstern decided to go to Petropavlovsk. In Petropavlovsk, the ambassador with the naturalist Langsdorf left the Nadezhda, and after a while Kruzenshtern went to continue exploring the shores of Sakhalin. Having reached the northern tip of the island, Nadezhda rounded Sakhalin and went along its western coast. In view of the fact that the deadline for departure to China was approaching, Kruzenshtern decided to return to Petropavlovsk in order to better prepare for this second part of the voyage.