The flammable composition, which could not be extinguished with water, was known to the ancient Greeks. “To burn enemy ships, a mixture of ignited resin, sulfur, tow, incense and sawdust of a resinous tree is used,” Aeneas Tacticus wrote in his essay “On the Art of a Commander” in 350 BC. In 424 BC, a certain combustible substance was used in the land battle of Delia: the Greeks from a hollow log sprayed fire in the direction of the enemy. Unfortunately, like many discoveries of Antiquity, the secrets of this weapon were lost, and the liquid unquenchable fire had to be reinvented.

This was done in 673 by Kallinikos, or Kallinikos, a resident of Heliopolis captured by the Arabs in the territory of modern Lebanon. This mechanic fled to Byzantium and offered his services and his invention to Emperor Constantine IV. The historian Theophanes wrote that the vessels with the mixture invented by Kallinikos were thrown by catapults at the Arabs during the siege of Constantinople. The liquid flared up on contact with air, and no one could extinguish the fire. The Arabs fled in horror from the weapon, which received the name "Greek fire".

Siphon with Greek fire on a mobile siege tower. (Pinterest)

Possibly, Kallinikos also invented a device for throwing fire, called a siphon, or siphonophore. These copper tubes, painted to look like dragons, were installed on the high decks of dromons. Under the influence of compressed air from the bellows, they threw a stream of fire into enemy ships with a terrible roar. The range of these flamethrowers did not exceed thirty meters, but for several centuries the enemy ships were afraid to come close to the Byzantine battleships. Handling Greek fire required extreme caution. The chronicles mention many cases when the Byzantines themselves died in an unquenchable flame due to broken vessels with a secret mixture.

Armed with Greek fire, Byzantium became the mistress of the seas. In 722, a major victory was won over the Arabs. In 941, an unquenchable flame drove the boats of the Russian prince Igor Rurikovich away from Constantinople. The secret weapon did not lose its significance two centuries later, when it was used against Venetian ships with participants in the Fourth Crusade on board.

It is not surprising that the secret of making Greek fire was strictly guarded by the Byzantine emperors. Lez the Philosopher ordered the mixture to be made only in secret laboratories under heavy guard. Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus wrote in his instructions to his heir: “You should most of all take care of the Greek fire ... and if anyone dares to ask you for it, as we often asked ourselves, then reject these requests and answer that the fire was opened by the Angel to Constantine, the first emperor of the Christians. The great emperor, as a warning to his heirs, ordered a curse to be carved in the temple on the throne for anyone who dares to convey this discovery to strangers ... ".

Terrible tales could not make Byzantium's competitors stop trying to discover the secret. In 1193, the Arab Saladan wrote: "Greek fire is" kerosene "(petroleum), sulfur, tar and tar." The recipe of the alchemist Vincetius (XIII century) is more detailed and exotic: “To get Greek fire, you need to take an equal amount of molten sulfur, tar, one fourth of opopanax (vegetable juice) and pigeon droppings; all this, well dried, is dissolved in turpentine or sulfuric acid, then placed in a strong closed glass vessel and heated for fifteen days in an oven. After that, the contents of the vessel should be distilled like wine alcohol and stored ready-made.

However, the mystery of Greek fire became known not thanks to scientific research, but because of a banal betrayal. In 1210, Emperor Alexei III Angel lost his throne and defected to the Konya sultan. He took care of the defector and made him commander of the army. Not surprisingly, just eight years later, crusader Oliver L'Ecolator testified that the Arabs used Greek fire against the crusaders during the siege of Damietta.

Alexei III Angel. (Pinterest)

Soon Greek fire ceased to be only Greek. The secret of its manufacture has become known different nations. The French historian Jean de Joinville, a member of the Seventh Crusade, personally came under fire during the Saracen assault on the fortifications of the crusaders: “The nature of Greek fire is this: its projectile is huge, like a vessel for vinegar, and the tail stretching behind looks like a giant spear. His flight was accompanied by a terrible noise, like thunder from heaven. The Greek fire in the air was like a dragon flying in the sky. Such a bright light emanated from it that it seemed that the sun had risen over the camp. The reason for this was the huge fiery mass and brilliance contained in it.

The Russian chronicles mention that the people of Vladimir and Novgorod, with the help of some kind of fire, enemy fortresses "set fire and there was a storm and a great smoke I will pull on these." Unquenchable flame was used by the Polovtsy, the Turks and the troops of Tamerlane. Greek fire ceased to be a secret weapon and lost its strategic importance. In the 14th century, he was almost never mentioned in the annals and chronicles. The last time Greek fire was used as a weapon was in 1453 during the capture of Constantinople. The historian Francis wrote that he was thrown at each other by both the Turks besieging the city and the defending Byzantines. At the same time, guns were also used on both sides, firing with conventional gunpowder. It was much more practical and safer than capricious liquid and quickly replaced Greek fire in military affairs.

Juan de Joinville. (Pinterest)

Only scientists have not lost interest in the self-igniting composition. In search of a recipe, they carefully studied the Byzantine chronicles. An entry made by Princess Anna Comnena was discovered, stating that the composition of the fire included only sulfur, resin and tree sap. Apparently, despite her noble birth, Anna was not privy to state secrets, and her recipe gave little to scientists. In January 1759, the French chemist and artillery commissar André Dupré announced that, after much research, he had discovered the secret of Greek fire. In Le Havre, with a huge gathering of people and in the presence of the king, tests were carried out. The catapult hurled a pot of resinous liquid at the sloop anchored in the sea, which immediately caught fire. Amazed, Louis XV ordered that all papers relating to his discovery be bought from Dupre and destroyed, hoping in this way to hide traces of dangerous weapons. Soon Dupre himself died under unclear circumstances. The recipe for Greek fire was again lost.

Disputes about the composition of medieval weapons continued into the 20th century. In 1937, the German chemist Stötbacher wrote in his book Gunpowder and Explosives that Greek fire consisted of "sulphur, salt, tar, asphalt and burnt lime". In 1960, the Englishman Partington, in his voluminous work The History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, suggested that the secret weapons of the Byzantines included light fractions of oil distillation, tar and sulfur. Furious disputes between him and his French colleagues were caused by the possible presence of saltpeter in the composition of the fire. Partington's opponents proved the presence of saltpeter by the fact that, according to the testimony of Arab chroniclers, it was possible to extinguish Greek fire only with the help of vinegar.

Today, the most likely version is the following composition of Greek fire: the crude product of the light fraction of oil distillation, various resins, vegetable oils and possibly saltpeter or quicklime. This recipe vaguely resembles a primitive version of modern napalm and flamethrower charges. So today's flamethrowers, Molotov cocktail throwers and Game of Thrones characters, constantly throwing fireballs at each other, can consider the medieval inventor Kallinikos as their progenitor.

In the year 6449 (941). Igor went to the Greeks. And the Bulgarians sent a message to the tsar that the Russians were going to Tsargrad: ten thousand ships. And they came, and sailed, and began to devastate the country of Bithynia, and captivated the land along the Pontic Sea to Heraclia and to the Paphlagonian land, and captivated the whole country of Nicomedia, and burned the whole Court. And those who were captured - some were crucified, while in others, as a goal, they shot with arrows, wringing their hands back, tied them up and drove iron nails into their heads. Many of the holy churches were set on fire, and on both banks of the Court they seized a lot of wealth. When the soldiers came from the east - Panfir-Demestik with forty thousand, Phocas-Patricius with the Macedonians, Fedor the Stratilat with the Thracians, and with them the dignitary boyars, they surrounded Russia. The Russians, having consulted, went out against the Greeks with weapons, and in a fierce battle the Greeks barely defeated. The Russians, by evening, returned to their squad and at night, sitting in the boats, sailed away. Theophanes met them in the boats with fire and began to fire with pipes on the Russian boats. And a terrible miracle was seen. The Russians, seeing the flames, threw themselves into the sea water, trying to escape, and so the rest returned home. And, having come to their land, they told - each to their own - about what had happened and about the boat fire. “It’s like lightning from heaven,” they said, “the Greeks have in their place, and by releasing it, they set fire to us; that is why they did not overcome them.” Igor, on his return, began to gather a lot of soldiers and sent across the sea to the Varangians, inviting them to the Greeks, again intending to go to them.

SO MUCH WONDERFUL FIRE, AS LIKE A HEAVENLY LIGHTNING

The chronicler knows the Russian tradition and the Greek news about Igor's campaign against Constantinople: in 941, the Russian prince went by sea to the shores of the Empire, the Bulgarians gave the news to Constantinople that Russia was coming; Protovestiary Theophanes was sent against her, who set Igor's boats on fire with Greek fire. Having suffered a defeat at sea, the Russians landed on the shores of Asia Minor and, as usual, greatly devastated them, but here they were caught and defeated by the patrician Barda and domestic John, rushed into the boats and set off to the shores of Thrace, were overtaken on the road, again defeated by Theophanes and with small the remnants returned back to Russia. At home, the fugitives justified themselves by saying that the Greeks had some kind of miraculous fire, like heavenly lightning, which they launched into Russian boats and burned them.

But on a dry path, what was the cause of their defeat? This reason can be discovered in the legend itself, from which it is clear that Igor's campaign was not like Oleg's enterprise, accomplished by the combined forces of many tribes; it was more like a raid by a gang, a small squad. The fact that there were few troops, and contemporaries attributed to this circumstance the cause of the failure, is shown by the words of the chronicler, who immediately after describing the campaign says that Igor, having come home, began to collect a large army, sent across the sea to hire the Varangians to go again to the Empire.

The chronicler places Igor's second campaign against the Greeks under the year 944; this time he says that Igor, like Oleg, gathered a lot of troops: the Varangians, Rus, Polyans, Slavs, Krivichi, Tivertsy, hired the Pechenegs, taking hostages from them, and went on a campaign on boats and horses to avenge the previous defeat . The people of Korsun sent a message to Emperor Roman: "Rus is advancing with countless ships, the ships have covered the whole sea." The Bulgarians also sent a message: “Rus is coming; hired and Pechenegs. Then, according to legend, the emperor sent his best boyars to Igor with a request: "Do not go, but take the tribute that Oleg took, I will give it to her." The emperor also sent expensive fabrics and a lot of gold to the Pechenegs. Igor, having reached the Danube, convened a squad and began to think with her about the proposals of the emperor; The squad said: “If the king says so, then why do we need more? Without fighting, let's take gold, silver and curtains! How do you know who wins, us or them? After all, it is impossible to agree with the sea in advance, we do not walk on land, but in the depths of the sea, one death to all. Igor obeyed the squad, ordered the Pechenegs to fight the Bulgarian land, took gold and curtains from the Greeks for himself and for the whole army, and went back to Kyiv. In the next year, 945, an agreement was concluded with the Greeks, also, apparently, to confirm the brief and, perhaps, verbal efforts concluded immediately after the end of the campaign.

Kyiv - CAPITAL, RULE - IGOR

In Igor's agreement with the Greeks, we read, among other things, that the Russian Grand Duke and his boyars can annually send as many ships to the great Greek kings as they want, with ambassadors and guests, i.e. with their own clerks and with free Russian merchants. This story of the Byzantine emperor clearly shows us the close connection between the annual turnover of political and economic life Russia. The tribute that the Kyiv prince collected as a ruler was at the same time the material of his trade turnover: having become a sovereign, like a koning, he, like a Varangian, did not cease to be an armed merchant. He shared tribute with his retinue, which served him as an instrument of government, constituted the government class. This class acted as the main lever, in both ways, both political and economic: in winter it ruled, walked among people, begged, and in summer it traded in what it collected during the winter. In the same story, Constantine vividly outlines the centralizing significance of Kyiv as the center of the political and economic life of the Russian land. Russia, the government class headed by the prince, with its overseas trade turnover supported the ship trade in the Slavic population of the entire Dnieper basin, which found a market for itself at the spring fair of one-trees near Kyiv, and every spring it pulled merchant boats here from different corners of the country along the Greek-Varangian route with the goods of forest hunters and beekeepers. Through such a complex economic cycle, a silver Arab dirhem or a gold clasp of Byzantine work fell from Baghdad or Constantinople to the banks of the Oka or Vazuza, where archaeologists find them.

swore by Perun

It is remarkable that the Varangian (Germanic) mythology did not have any influence on the Slavic, despite the political domination of the Varangians; it was so for the reason that the pagan beliefs of the Varangians were neither clearer nor stronger than the Slavic ones: the Varangians very easily changed their paganism to the Slavic cult if they did not accept Greek Christianity. Prince Igor, a Varangian by origin, and his Varangian squad already swore by the Slavic Perun and worshiped his idol.

"DO NOT GO, BUT TAKE A TRIBUTE"

One of the reasons for the catastrophic defeat of "Tsar" Helg and Prince Igor in 941 was that they could not find allies for the war with Byzantium. Khazaria was absorbed in the struggle against the Pechenegs and could not provide effective assistance to the Rus.

In 944 Prince Igor of Kyiv undertook a second campaign against Constantinople. The Kyiv chronicler did not find any mention of this enterprise in Byzantine sources, and in order to describe a new military expedition, he had to "paraphrase" the story of the first campaign.

Igor failed to take the Greeks by surprise. The Korsunians and Bulgarians managed to warn Constantinople of the danger. The emperor sent “the best boyars” to Igor, imploring him: “Don’t go, but take tribute, Oleg had the south, I’ll give it to that tribute.” Taking advantage of this, Igor accepted the tribute and left "in his own way." The chronicler was sure that the Greeks were frightened by the power of the Russian fleet, for Igor's ships covered the entire sea "scissorless". In fact, the Byzantines were worried not so much by the fleet of the Rus, the recent defeat of which they did not forget, but by Igor's alliance with the Pecheneg horde. The pastures of the Pecheneg Horde spread over a vast area from the Lower Don to the Dnieper. The Pechenegs became the dominant force in the Black Sea region. According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, the attacks of the Pechenegs deprived the Rus of the opportunity to fight with Byzantium. The peace between the Pechenegs and the Rus was fraught with a threat to the empire.

Preparing for a war with Byzantium, the Kyiv prince "hired" the Pechenegs, i.e. sent rich gifts to their leaders, and took hostages from them. Having received tribute from the emperor, the Rus sailed to the east, but first Igor "ordered the Pechenegs to fight the Bulgarian land." The Pechenegs were pushed to the war against the Bulgarians, perhaps not only by the Rus, but also by the Greeks. Byzantium did not give up its intention to weaken Bulgaria and again subjugate it to its power. Having completed hostilities, the Russians and Greeks exchanged embassies and concluded a peace treaty. It follows from the agreement that the sphere of special interests of Byzantium and Russia was the Crimea. The situation on the Crimean peninsula was determined by two factors: the long-standing Byzantine-Khazar conflict and the emergence of a Norman principality at the junction of Byzantine and Khazar possessions. Chersonese (Korsun) remained the main stronghold of the empire in the Crimea. It was forbidden for a Russian prince to "have volosts", i.e., to seize the possessions of the Khazars in the Crimea. Moreover, the treaty obliged the Russian prince to fight ("let him fight") with the enemies of Byzantium in the Crimea. If “that country” (the Khazar possessions) did not submit, in this case the emperor promised to send his troops to help the Rus. In fact, Byzantium set the goal of expelling the Khazars from the Crimea with the hands of the Rus, and then dividing them from the possession. The agreement was implemented, albeit with a delay of more than half a century. The Kyiv principality got Tmutarakan with the cities of Tamatarkha and Kerch, and Byzantium conquered the last possessions of the Khazars around Surozh. At the same time, King Sfeng, the uncle of the Kyiv prince, provided direct assistance to the Byzantines ...

Peace treaties with the Greeks created favorable conditions for the development of trade and diplomatic relations between Kievan Rus and Byzantium. Russ received the right to equip any number of ships and trade in the markets of Constantinople. Oleg had to agree that the Russians, no matter how many of them came to Byzantium, have the right to enter the service in the imperial army without any permission from the Kyiv prince ...

The peace treaties created the conditions for the penetration of Christian ideas into Russia. At the conclusion of the treaty in 911, there was not a single Christian among Oleg's ambassadors. The Rus sealed the “haratya” with an oath to Perun. In 944, in addition to pagan Rus, Christian Rus also participated in negotiations with the Greeks. The Byzantines singled them out, giving them the right to be the first to take the oath and taking them to the "cathedral church" - St. Sophia Cathedral.

The study of the text of the treaty allowed M. D. Priselkov to assume that already under Igor, power in Kyiv actually belonged to the Christian party, to which the prince himself belonged, and that negotiations in Constantinople led to the development of conditions for the establishment of a new faith in Kyiv. This assumption cannot be reconciled with the source. One of the important articles of the treaty of 944 read: “If a Khrestian kills a Rusyn, or a Rusyn Christian,” etc. The article certifies that the Rusyns belong to the pagan faith. Russian ambassadors lived in Constantinople for a long time: they had to sell the goods they brought. The Greeks used this circumstance to convert some of them to Christianity... The agreement of 944 drawn up by experienced Byzantine diplomats provided for the possibility of adopting Christianity by the "princes" who remained during the negotiations in Kyiv. The final formula read: “And to transgress this (agreement - R. S.) from our country (Rus. - R. S.), whether it is a prince, whether someone is baptized, whether they are not baptized, but they do not have help from God .. .»; who violated the agreement "let there be an oath from God and from Perun."

Skrynnikov R.G. Old Russian state

THE TOP OF OLD RUSSIAN DIPLOMACY

But what an amazing thing! This time, Russia insisted - and it is difficult to find another word here - for the appearance of Byzantine ambassadors in Kyiv. The period of discrimination against the northern “barbarians” has ended, who, despite their high-profile victories, obediently wandered to Constantinople for negotiations and here, under the vigilant gaze of the Byzantine clerks, formulated their contractual requirements, put their speeches on paper, diligently translated diplomatic stereotypes unfamiliar to them from Greek, and then they gazed in fascination at the magnificence of the temples and palaces of Constantinople.

Now the Byzantine ambassadors had to come to Kyiv for the first talks, and it is difficult to overestimate the importance and prestige of the agreement reached. …

In essence, the tangle of the entire East European policy of those days was unwound here, in which Russia, Byzantium, Bulgaria, Hungary, the Pechenegs and, possibly, Khazaria were involved. Negotiations took place here, new diplomatic stereotypes were developed, the foundation was laid for a new long-term agreement with the empire, which was supposed to regulate relations between countries, reconcile or, at least, smooth out the contradictions between them ...

And then the Russian ambassadors moved to Constantinople.

It was a big embassy. Gone are the days when the five Russian ambassadors opposed the entire Byzantine diplomatic routine. Now a prestigious representation of a powerful state was sent to Constantinople, consisting of 51 people - 25 ambassadors and 26 merchants. They were accompanied by armed guards, shipbuilders ...

The title of the Russian Grand Duke Igor sounded differently in the new treaty. The epithet “bright” was lost and disappeared somewhere, which the Byzantine clerks awarded Oleg with such far from naive calculation. In Kyiv, apparently, they quickly figured out what was happening and realized in what unenviable position he put the Kyiv prince. Now, in the treaty of 944, this title is not present, but Igor is referred to here as in his homeland - "the Grand Duke of Russia." True, sometimes in articles, so to speak, in the working order, the concepts of "grand prince" and "prince" are also used. And yet it is quite obvious that Russia also tried to achieve a change here and insisted on the title that did not infringe on her state dignity, although, of course, he was still far from such heights as "king" and emperor "...

Russia, step by step, slowly and stubbornly won diplomatic positions for itself. But this was most clearly reflected in the procedure for signing and approving the treaty, as stated in the treaty. This text is so remarkable that it is tempting to quote it in its entirety...

For the first time we see that the treaty was signed by the Byzantine emperors, for the first time the Byzantine side was instructed by the treaty to send its representatives back to Kyiv in order to take an oath on the treaty by the Russian Grand Duke and his husbands. For the first time, Russia and Byzantium assume equal obligations regarding the approval of the treaty. Thus, from the beginning of the development of a new diplomatic document until the very end of this work, Russia was on an equal footing with the empire, and this itself was already a remarkable phenomenon in the history of Eastern Europe.

And the treaty itself, which both sides worked out with such care, became an extraordinary event. The diplomacy of that time does not know a document of a larger scale, more detailed, embracing economic, political, and military-allied relations between countries.

Information about the use of flamethrowers dates back to antiquity. Then these technologies were borrowed by the Byzantine army. The Romans somehow set fire to the enemy fleet already in 618, during the siege of Constantinople, undertaken by the Avar Khagan in alliance with the Iranian Shah Khosrow II. The besiegers used the Slavic naval flotilla for the crossing, which was burned in the Golden Horn.

A warrior with a hand-held flamethrower siphon. From the Vatican manuscript of "Polyorcetics" by Heron of Byzantium(Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1605). IX-XI centuries

The inventor of the "Greek fire" was the Syrian engineer Kallinikos, a refugee from Heliopolis captured by the Arabs (modern Baalbek in Lebanon). In 673, he demonstrated his invention to Vasileus Constantine IV and was accepted into the service.

It was a truly infernal weapon, from which there was no escape: "liquid fire" burned even on water.

The basis of "liquid fire" was natural pure oil. Its exact recipe remains a secret to this day. However, the technology of using a combustible mixture was much more important. It was necessary to accurately determine the degree of heating of the hermetically sealed boiler and the force of pressure on the surface of the air mixture pumped with the help of bellows. The cauldron was connected to a special siphon, to the opening of which an open fire was brought at the right moment, the faucet of the cauldron was opened, and the combustible liquid, ignited, poured out onto enemy ships or siege engines. Siphons were usually made of bronze. The length of the fiery stream erupted by them did not exceed 25 meters.

Siphon for "Greek fire"

Oil for "liquid fire" was also mined in the Northern Black Sea and Azov regions, where archaeologists find in abundance shards from Byzantine amphorae with resinous sediment on the walls. These amphoras served as containers for the transportation of oil, identical in chemical composition Kerch and Taman.

The invention of Kallinikos was tested in the same year 673, when with his help the Arab fleet, which first laid siege to Constantinople, was destroyed. According to the Byzantine historian Theophanes, "the Arabs were shocked" and "fled in great fear."

byzantine ship,armed with "Greek fire", attacks the enemy.

Miniature from the "Chronicle" of John Skylitzes (MS Graecus Vitr. 26-2). 12th century Madrid, Spanish National Library

Since then, "liquid fire" has repeatedly rescued the capital of Byzantium and helped the Romans win battles. Vasilevs Leo VI the Wise (866-912) proudly wrote: “We have various means, both old and new, to destroy enemy ships and people fighting on them. This is the fire prepared for the siphons, from which it rushes about with a thunderous noise and smoke, burning the ships to which we direct it.

The Rus first became acquainted with the action of "liquid fire" during the campaign against Constantinople by Prince Igor in 941. Then the capital of the Roman state was besieged by a large Russian fleet - about two hundred and fifty boats. The city was blocked from land and from the sea. The Byzantine fleet at that time was far from the capital, fighting with Arab pirates in the Mediterranean. At hand, the Byzantine emperor Roman I Lecapenus had only a dozen and a half ships, decommissioned ashore due to dilapidation. Nevertheless, the basileus decided to give the Russians a battle. Siphons with "Greek fire" were installed on half-rotten vessels.

Seeing the Greek ships, the Russians raised their sails and rushed towards them. The Romans were waiting for them in the Golden Horn.

The Rus boldly approached the Greek ships, intending to board them. Russian boats stuck around the ship of the Roman naval commander Theophan, who was ahead of the battle formation of the Greeks. At this moment, the wind suddenly died down, the sea was completely calm. Now the Greeks could use their flamethrowers without interference. The instant change in the weather was perceived by them as help from above. Greek sailors and soldiers perked up. And from the ship of Feofan, surrounded by Russian boats, fiery jets poured in all directions. The flammable liquid spilled over the water. The sea around the Russian ships seemed to suddenly flare up; several rooks blazed at once.

The action of the terrible weapon shocked the Igor warriors to the core. In an instant, all their courage disappeared, panic fear seized the Russians. “Seeing this,” writes a contemporary of the events, Bishop Liutprand of Cremona, “the Russians immediately began to rush from ships into the sea, preferring to drown in the waves rather than burn out in flames. Others, burdened with shells and helmets, went to the bottom, and they were no longer seen, while some that kept afloat burned down even in the midst of the sea waves. The Greek ships that arrived in time "completed the rout, sank many ships along with the crew, killed many, and took even more alive" (Theophan's successor). Igor, as Leo the Deacon testifies, escaped with "hardly a dozen rooks", which managed to land on the shore.

This is how our ancestors got acquainted with what we now call the superiority of advanced technologies.

"Olyadny" (Olyadiya in Old Russian - a boat, a ship) fire for a long time became a byword in Russia. The Life of Basil the New says that the Russian soldiers returned to their homeland "to tell what happened to them and what they suffered at the behest of God." The “Tale of Bygone Years” brought the living voices of these people scorched by fire to us: “Those who returned to their land told about what happened; and they said about deer fire that the Greeks have this heavenly lightning at home; and, letting it go, they burned us, and for this reason they did not overcome them. These stories are indelibly etched in the memory of the Rus. Leo the Deacon reports that even thirty years later, the soldiers of Svyatoslav still could not remember the liquid fire without shivering, since “they heard from their elders” that the Greeks turned Igor’s fleet into ashes with this fire.

View of Constantinople. Drawing from the Nuremberg Chronicle. 1493

It took a whole century for the fear to be forgotten, and the Russian fleet again dared to approach the walls of Constantinople. This time it was the army of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, led by his son Vladimir.

In the second half of July 1043, the Russian flotilla entered the Bosporus and occupied the harbor on the right bank of the strait, opposite the Golden Horn Bay, where, under the protection of heavy chains that blocked the entrance to the bay, the Roman fleet was laid up. On the same day, Vasilevs Constantine IX Monomakh ordered all cash to be prepared for the battle. naval forces- not only combat triremes, but also cargo ships, on which siphons with "liquid fire" were installed. Troops of cavalry were sent out along the coast. Toward night, the basileus, according to the Byzantine chronicler Michael Psellos, solemnly announced to the Rus that tomorrow he intended to give them a sea battle.

With the first rays of the sun breaking through the morning fog, the inhabitants of the Byzantine capital saw hundreds of Russian boats built in one line from coast to coast. “And there was not a person among us,” says Psellus, “who looked at what was happening without the strongest spiritual anxiety. I myself, standing near the autocrat (he was sitting on a hill, sloping down to the sea), watched the events from a distance. Apparently, this frightening spectacle made an impression on Constantine IX. Having ordered his fleet to line up in battle formation, he, however, hesitated to give the signal for the start of the battle.

Hours dragged on in inaction. Long past noon, and the chain of Russian boats still swayed on the waves of the strait, waiting for the Roman ships to leave the bay. Only when the sun began to go down did the basileus, overcoming his indecision, finally ordered Master Basil Theodorokan to leave the bay with two or three ships in order to draw the enemy into battle. “They swam forward lightly and harmoniously,” says Psellos, “spearmen and stone-throwers raised a battle cry on their decks, fire-throwers took their places and prepared to act. But at this time, many barbarian boats, separated from the rest of the fleet, rushed at high speed towards our ships. Then the barbarians divided up, surrounded each of the triremes on all sides and began to make holes in the Roman ships from below with their peaks; ours at that time threw stones and spears at them from above. When the fire that burned their eyes flew into the enemy, some barbarians rushed into the sea to swim to their own, others were completely desperate and could not figure out how to escape.

According to Skylitsa, Vasily Theodorokan burned 7 Russian boats, sank 3 together with people, and captured one, jumping into it with a weapon in his hands and engaging in battle with the Russians who were there, from which some were killed by him, while others rushed into the water.

Seeing the successful actions of the master, Constantine signaled the advance of the entire Roman fleet. Fire-bearing triremes, surrounded by smaller ships, escaped from the Golden Horn Bay and rushed to the Rus. The latter, obviously, were discouraged by the unexpectedly large number of the Roman squadron. Psellos recalls that “when the triremes crossed the sea and ended up at the very canoes, the barbarian system crumbled, the chain broke, some ships dared to stay in place, but most of them fled.”

In the gathering twilight, the bulk of the Russian boats left the Bosporus Strait for the Black Sea, probably hoping to hide from pursuit in shallow coastal waters. Unfortunately, just at that time, a strong east wind arose, which, according to Psellos, “furrowed the sea with waves and drove water shafts against the barbarians. Some ships were immediately covered by the rearing waves, while others were dragged along the sea for a long time and then thrown onto the rocks and onto the steep coast; our triremes set off in pursuit of some of them, they launched some boats under the water along with the crew, and other soldiers from the triremes made a hole and half-flooded delivered to the nearest shore. Russian chronicles tell that the wind "broke" the "prince's ship", but Ivan Tvorimirich, who came to the rescue of the voivode, saved Vladimir by taking him into his boat. The rest of the warriors had to escape as best they could. Many of those who reached the shore died under the hooves of the Roman cavalry who arrived in time. “And then they gave the barbarians a true bloodletting,” Psellus concludes his story, “it seemed as if a stream of blood poured out of the rivers colored the sea.”

§ 1 The first Russian princes. Oleg

The formation of the Old Russian state is associated with the activities of the first Kyiv princes: Oleg, Igor, Princess Olga and Svyatoslav. Each of them contributed to the formation of the Old Russian state. The activities of the first Kyiv princes were subordinated to two main goals: to extend their power to all East Slavic tribes and to profitably sell goods during the polyud. To do this, it was necessary to maintain trade relations with other countries and protect trade routes from robbers who robbed merchant caravans.

The most profitable trade for merchants Kievan Rus was with Byzantium - the richest European state of that time. So Kyiv princes repeatedly made military campaigns against the capital Constantinople (Tsargrad) in order to restore or maintain trade relations with Byzantium. The first was Prince Oleg, contemporaries called him Prophetic. Having made successful campaigns against Constantinople in 907 and 911, he defeated the Byzantines and nailed his shield to the gates of Constantinople. The result of the campaigns was the signing of a profitable trade agreement on duty-free trade for Russian merchants in Byzantium.

The legend says that Prince Oleg died from a snake bite that crawled out of the fallen skull of his beloved horse.

§ 2 Igor and Olga

After the death of Oleg, Rurik's son Igor became the Prince of Kyiv. He began his reign with the return of the Drevlyans to the rule of Kyiv, who separated, taking advantage of the death of Oleg.

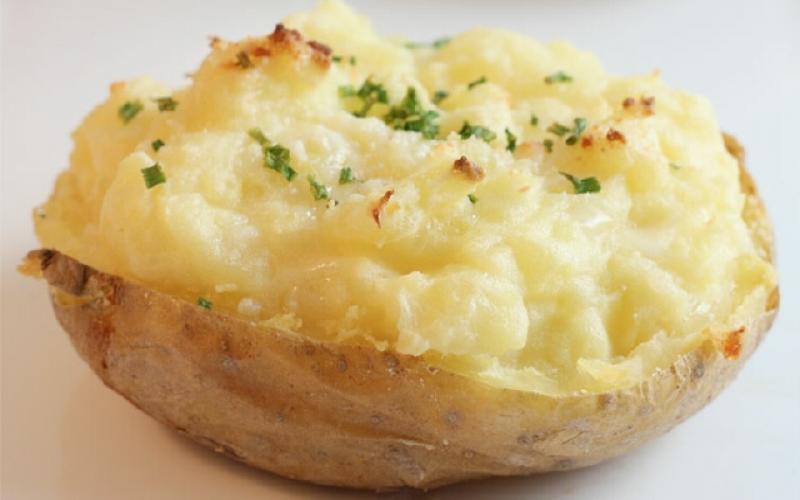

In 941, Igor made a military campaign against Constantinople. But he was unsuccessful. The Byzantines burned the boats of the Rus with a combustible mixture, "Greek fire."

In 944, Igor again went to Byzantium. The result of the campaign was a new trade agreement concluded by him, which contained a number of restrictions for Russian merchants.

In 945, Igor and his retinue made polyudye. Having already collected tribute and returning to Kyiv, Igor decided that the payment of the Drevlyans was small. The prince released most of the squad to Kyiv and returned to the Drevlyans demanding a new tribute. The Drevlyans were outraged, the prince grossly violated the terms of the polyudye agreement. They gathered a veche, which decided: "If a wolf has got into the habit of sheep, then it will carry away the whole herd until they kill it." The warriors were killed, and the prince was executed.

After the death of Prince Igor, his widow Princess Olga became the ruler of Kyiv. She cruelly avenged the Drevlyans for the death of her husband and the father of their son Svyatoslav. The ambassadors of the Drevlyan prince Mala ordered to be buried alive near the walls of Kyiv, and the city of Iskorosten, the capital of the Drevlyans, was burned to the ground. So that events like the massacre with Igor would not be repeated, the princess carried out a tax reform (transformation): she established fixed rates for collecting tribute - lessons and places for collecting it - graveyards.

In 957, Olga was the first of the princely family to accept Christianity in Byzantium, setting an example for other princes.

§ 3 Svyatoslav

Returning from Byzantium, Olga transfers the reign to her son Svyatoslav. Svyatoslav went down in history as a great commander of the Old Russian state.

Svyatoslav was of medium height, not hefty in strength, broad in the shoulders, with a powerful neck. He shaved his head baldly, leaving only a strand of hair on his forehead - a sign of the nobility of the family, in one ear he wore an earring with pearls and a ruby. Gloomy, despising any comfort, he shared all the hardships of the campaign with his warriors: he slept on the ground under the open sky, ate thinly sliced meat cooked on coals, participated in battle on equal terms, fought furiously, cruelly, uttering a wild, frightening roar. He was distinguished by nobility, always, going to the enemy, he warned: "I'm going to you"

The people of Kiev often reproached him: "You are looking for the prince of a foreign land, but you forget about your own land." Indeed, Svyatoslav spent most of his time on campaigns than in Kyiv. He annexed the lands of the Vyatichi to Russia, made a trip to the Volga Bulgaria, defeated Khazaria, which prevented Russian merchants from trading along the Volga and the Caspian Sea with Eastern countries. Then Svyatoslav and his retinue captured the mouth of the Kuban River and the coast of the Sea of Azov. There he formed the Tmutarakan principality, dependent on Russia.

Svyatoslav also made successful campaigns in a southwestern direction to the territory of modern Bulgaria. He captured the city of Pereslavets, planning to move the capital of Russia here. This aroused the concern of the Byzantines, at whose borders a new strong enemy appeared. The emperor of Byzantium persuaded his Pecheneg allies to attack Kyiv, where Svyatoslav's mother, Princess Olga, and her grandchildren were, forcing Svyatoslav to return home and abandon the campaign against Byzantium.

In 972, Svyatoslav, returning home, was ambushed by the Pechenegs at the Dnieper rapids (stone heaps, on the river) and was killed. The Pecheneg Khan ordered to make a cup in a gold frame from the skull of Svyatoslav, from which he drank wine, celebrating his victories.

§ 4 Lesson summary

The formation of the Old Russian state is connected with the first princes of Kyiv: Oleg, Igor, Olga, Svyatoslav.

Oleg in 882 founded a single Old Russian state.

The Rurik dynasty begins with Igor.

Olga carried out a tax reform and was the first of the princely family to accept Christianity.

Svyatoslav as a result of military campaigns expanded the territory of Kievan Rus

Used images:

The term "Greek fire" was not used in the Greek language, nor in the languages of the Muslim peoples, it arises from the moment when Western Christians became acquainted with it during the Crusades. The Byzantines and Arabs themselves called it differently: "liquid fire", "sea fire", "artificial fire" or "Roman fire". Let me remind you that the Byzantines called themselves "Romans", i.e. the Romans.

The invention of "Greek fire" is attributed to the Greek mechanic and architect Kalinnik, a native of Syria. In 673, he offered it to the Byzantine emperor Constantine IV Pogonatus (654-685) for use against the Arabs who were besieging Constantinople at that time.

"Greek fire" was used primarily in naval battles as an incendiary, and according to some sources, as an explosive.

The recipe for the mixture has not been preserved for certain, but according to fragmentary information from various sources, it can be assumed that it included oil with the addition of sulfur and nitrate. In the "Fire Book" of Mark the Greek, published in Constantinople at the end of the 13th century, the following composition of Greek fire is given: bay oil, then put in a pipe or in a wooden trunk and light. The charge immediately flies in any direction and destroys everything with fire. "It should be noted that this composition served only to eject a fire mixture in which an "unknown ingredient" was used. Some researchers suggested that quicklime could be the missing ingredient. Other possible components asphalt, bitumen, phosphorus, etc. were offered.

It was impossible to extinguish the "Greek fire" with water; attempts to extinguish it with water only led to an increase in the combustion temperature. However, subsequently, means were found to combat the "Greek fire" with the help of sand and vinegar.

"Greek fire" was lighter than water and could burn on its surface, which gave the eyewitnesses the impression that the sea was on fire.

In 674 and 718 AD "Greek fire" destroyed the ships of the Arab fleet that besieged Constantinople. In 941, it was successfully used against the ships of the Rus during the unsuccessful campaign of the Kyiv prince Igor against Constantinople (Tsargrad). Preserved detailed description the use of "Greek fire" in the battle with the Pisan fleet off the island of Rhodes in 1103.

"Greek fire" was thrown out with the help of throwing pipes operating on the principle of a siphon, or a burning mixture in clay vessels was fired from a ballista or other throwing machine.

For throwing Greek fire, long poles were also used, mounted on special masts, as shown in the figure.

The Byzantine princess and writer Anna Komnena (1083 - c. 1148) reports the following about the pipes or siphons installed on the Byzantine warships (dromons): "On the bow of each ship were the heads of lions or other land animals, made of bronze or iron and gilded, moreover, so terrible that it was terrible to look at them; they arranged those heads in such a way that fire would erupt from their open mouths, and this was done by soldiers with the help of obedient mechanisms.

The range of the Byzantine "flamethrower" probably did not exceed a few meters, which, however, made it possible to use it in a naval battle at close range or in the defense of fortresses against the wooden siege structures of the enemy.

Scheme of the siphon device for throwing "Greek fire" (reconstruction)

Emperor Leo VI the Philosopher (870-912) writes about the use of "Greek fire" in naval combat. In addition, in his treatise "Tactics", he orders officers to use the recently invented hand pipes, and recommends spewing fire from them under the cover of iron shields.

Hand siphons are depicted in several miniatures. It is difficult to say anything definite about their device based on the images. Apparently, they were something like a spray gun, which used the energy of compressed air pumped with the help of bellows.

"Flamethrower" with a manual siphon during the siege of the city (Byzantine miniature)

The composition of the "Greek fire" was a state secret, so even the recipe for making the mixture was not recorded. Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (905 - 959) wrote to his son that he was obliged "first of all to direct all his attention to the liquid fire thrown out through pipes; and if they dare to ask you about this secret, as it often happened to me yourself, you must refuse and reject any prayers, pointing out that this fire was bestowed and explained by an angel to the great and holy Christian emperor Constantine.

Miniature of the Madrid copy of the "Chronicle" of John Skylitzes (XIII century)

Although no state, except Byzantium, possessed the secret of "Greek fire", various imitations of it have been used by Muslims and crusaders since the time of the Crusades.

The use of an analogue of "Greek fire" in the defense of the fortress (medieval English miniature)

The once formidable Byzantine navy gradually fell into disrepair, and the secret of true "Greek fire" may have been lost. In any case, during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, he did not help the defenders of Constantinople in any way.

Experts assess the effectiveness of "Greek fire" differently. Some even consider it more of a psychological weapon. With the beginning of the mass use of gunpowder (XIV century), "Greek fire" and other combustible mixtures lost their military significance and were gradually forgotten.

The search for the secret of "Greek fire" was carried out by medieval alchemists, and then by many researchers, but did not give unambiguous results. Probably its exact composition will never be established.

Greek fire became the prototype of modern napalm mixtures and a flamethrower.